We explain what the Byzantine Empire was and explore its history. In addition, we discuss the territories it comprised and the characteristics of the empire.

What was the Byzantine Empire?

The Byzantine Empire, also known as the Eastern Roman Empire or Byzantium, was a division of the Roman Empire that survived throughout the Middle Ages. Situated on the eastern shores of the Mediterranean Sea, its capital city was Constantinople (present-day Istanbul, Turkey).

Byzantium was a multi-ethnic Christian State that had a significant cultural, economic and political influence in the contemporary world. Byzantines considered themselves heirs of the Roman Empire and referred to themselves as Romans. However, over time, it distinguished itself from the Western Roman Empire due to its distinct political, cultural, and religious characteristics.

The Byzantine Empire existed between 285 and 1453 AD, and during the Middle Ages, acted as a barrier against the expansion of Islam into Europe. The history of Byzantium is often interpreted as a symbol of the widening gulf between Western and Eastern cultures in world history.

- See also: Roman Empire

Geographical location of the Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire encompassed mainly the territories of modern-day Turkey and Greece. At various points in its history, its territorial extent also comprised the eastern coast of the Mediterranean Sea, parts of Egypt, and certain regions of Italy.

Political organization of the Byzantine Empire

In Byzantium, the Greek term basileus (meaning "king") was used to refer to the emperor. The office was not hereditary but was determined by a selection procedure involving the Senate, the army, and representatives of the people. Over time, this procedure took on religious overtones, and the figure of the basileus acquired a divine character.

The Byzantine government was autocratic: the basileus imposed his power over all aspects of the lives of his citizens. He was at the head of the administration and the army, created laws and had them drafted, and was the supreme judge in important matters.

For the administration of the Empire, the basileus relied on a group of officials who constituted a hierarchically organized bureaucracy.

Economy of the Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine economy was based on agriculture, trade, and tax collection. The principal agricultural products were wheat, legumes, honey, wine, and nuts.

Byzantium came to develop long-distance trade with various regions of Asia and North Africa. Constantinople, the capital of the empire, became the center of large trade networks. The main imported products were wheat (as sustenance for urban populations) and silk (as a luxury item for the urban upper classes).

In addition, the Byzantine State levied taxes on much of the population. Most of the tax revenue was invested in the army.

Society in the Byzantine Empire

The population of the empire was diverse, and historians estimate that at its peak it would have reached 34 million inhabitants.

The majority of the population were peasants, and there were great inequalities in relation to land ownership. Some owned small plots of land for cultivation, which allowed them to sustain their families and pay state taxes. Others did not own land and worked in other people's fields in exchange for a wage. In addition, there were large landowners who gradually began to incorporate the plots of impoverished peasants.

Religion in the Byzantine Empire

Most of the population practiced the Christian religion. Christianity in Byzantium developed unique features and, over time, began to diverge from Western Christianity, whose center of power was Rome.

A dispute arose in Byzantium between different currents of religious interpretation. Most churches were decorated with images depicting Christ, the Virgin Mary, and saints in biblical scenes. In the early 8th century AD, a group of believers known as iconoclasts began to oppose the use of religious images, considering it a pagan practice.

Between 720 and 843 AD, Byzantine emperors adopted the iconoclastic trend: they prohibited and destroyed religious representations, replacing them with crosses. Nevertheless, in the mid-9th century, the use of religious images was reinstated.

Towards the 11th century, the "Great Schism" occurred within the Christian Church, by which the Eastern and Western Churches became separate institutions. The Byzantine Church became known as the Orthodox Church: Byzantines believed they adhered more faithfully to Christian doctrine than Western Christians. Although the difference between the two churches was grounded in doctrinal issues (i.e. how to interpret and practice the Christian faith), the reasons for the separation were eminently political.

History of the Byzantine Empire

Throughout its history, the Byzantine Empire underwent several important moments:

Origin of the Byzantine Empire

In the late 3rd century, facing the continuous political and economic crisis of the Roman Empire, Emperor Diocletian decided to divide the empire in two, in order to facilitate its control and administration. Each half was governed by an augustus and a caesar. This system is known as the tetrarchy.

This model remained in place until Diocletian's death, later resulting in a series of internal wars that Emperor Constantine I put an end to by unifying both halves of the empire and establishing Byzantium as the new capital (named "New Rome" but popularly known as Constantinopolis, the city of Constantine). In 395 AD, upon the death of Theodosius I, the empire again became divided. Each of his sons inherited a part: Flavius Honorius ruled over the Western Empire, with capital in Rome, and Arcadius ruled over the Eastern Empire, with capital in Byzantium.

In 476 AD, the Western Roman Empire fell to the attack of Germanic tribes and the capture of the city of Rome. However, the Eastern Roman Empire continued to maintain its political unity and its history lasted almost another thousand years, until its conquest by the Ottoman Empire in 1453 AD.

Reign of Justinian

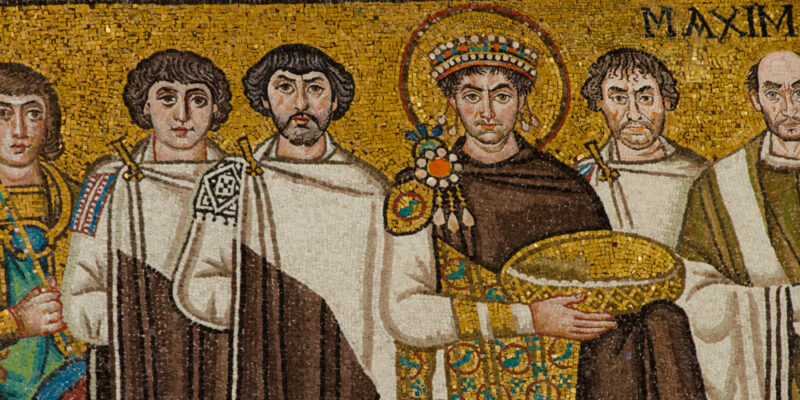

The height of the Byzantine Empire occurred during the reign of Justinian I, in the 6th century. The victory over the Persians on the empire’s eastern frontier allowed Byzantium to undertake a campaign to recover the territories of the former Roman Empire, which following its disintegration was now divided among various Germanic kingdoms. Thus, the Byzantine Empire conquered the Mediterranean coasts of North Africa, Italy, and southern Spain.

This epoch was marked by cultural splendor, epitomized by the temple of Hagia Sophia, erected in Byzantium as a symbol of imperial renaissance. However, the war efforts took their toll. The following century saw the empire plunge into an economic crisis and plague that wiped out a third of Constantinople's population.

Border instability

The 6th and 7th centuries AD were times of crisis for the Eastern Roman Empire, besieged on multiple borders by various enemies: the Persians resumed their struggle in the east, the Bulgarians and Slavs in the north, and Islam conquered the empire's richest territories in the Middle East: Syria, Palestine, and Egypt.

Emperors succeeded one another on the throne without being able to restore imperial strength, ceding to barbarian conquests the Tiber River and nearly all of Italy, and even defending Constantinople from the siege of the Avars and the Slavs in 626 AD.

Moreover, several internal conflicts related especially to religious affairs added to the situation.

Macedonian Renaissance

This period was followed by a significant recovery of the Empire, ruled by a dynasty of Macedonian kings and characterized by the estrangement between Eastern and Western Christianity.

During the 11th century, political influence over religious matters led to what is known as the "Great Schism" of Christianity, with the mutual excommunication of Pope Nicholas I and the Patriarch of Constantinople, Photius. This formalized the separation of the Eastern and Western Churches.

Decline of the Byzantine Empire

Towards the end of the 13th century AD, the empire entered a crisis that culminated in its eventual fall in 1453 AD. Scholars identify various causes for the weakening of the Byzantine Empire:

- The bureaucratic and tax system led large landowners to accumulate more lands while peasants lost their small properties. The empowerment of local landowners weakened their dependence on the emperor and, consequently, their obedience.

- Large landowners made use of their power to evade tax payment, and in turn, impoverished peasants saw their capacity to pay tributes reduced.

- Lower tax revenue forced a decrease in investment in the imperial army. Faced with the pressure of invasion at the borders and the outbreak of civil wars over internal power disputes, the weakened imperial army was unable to sustain the emperor's power.

During the final century of Byzantium, the Ottoman Empire gradually conquered much of its territory. In 1453, the city of Constantinople was besieged for six weeks until it was finally taken by the Ottoman Turks, bringing the Byzantine Empire to an end.

Culture in the Byzantine Empire

Among the main features of Byzantine culture are:

- Architecture. Byzantine architecture was noted for the construction of civil and religious buildings in its main urban centers. Numerous Christian churches were built in the city of Constantinople. The Hagia Sophia Church (dedicated to the "divine wisdom") was commissioned by Emperor Justinian I and stands as the pinnacle of the "Golden Age" of Byzantine architecture. It is characterized by its enormous dome and boasts having been the world's largest cathedral for over a millennium.

- Art. Byzantine art excelled in sculpture, painting, and mosaic work. The beauty of the mosaic work covering the walls of Byzantine churches is particularly renowned.

- Identity. Byzantium considered itself heir to the Roman Empire and was called Basileia Rhōmaiōn (Greek for "Roman Empire"). Its inhabitants referred to themselves as Romioi (Greek for "Roman"). The term "Byzantine Empire" came to be used only later by historians towards the 16th century to differentiate it from the earlier Roman Empire.

- Language. The original language of the Roman Empire was Latin. However, with the separation from the West, Latin was replaced by Greek. Eventually, the Byzantine Empire became the principal state that preserved classical Greek culture.

- Eastern influence. The Byzantine Empire adopted features from Eastern cultures, with which it shared borders and engaged in trade. Many historians recognize this influence in the accumulation of power and the divine traits of the emperor's figure.

Explore next:

References

- Chrysos, E. (2004). El imperio bizantino 565-1025 (Vol. 21). Icaria Editorial.

- Treadgold, W. (2001). Breve historia de Bizancio. Ediciones Paidós Ibérica

- Maier, F. (1987). Bizancio. Siglo XXI

- Patlagean, E., Ducellier, A., Asdracha, C., Mantran, R. (2003). Historia de Bizancio. Editorial Crítica.

Was this information useful to you?

Yes NoThank you for visiting us :)