We explain what feudalism was, and how society was divided at the time. In addition, we explore the basis of feudal economy, and its characteristics.

What was feudalism?

Feudalism was a social system that emerged in the Frankish kingdom in the Early Middle Ages and spread throughout Western Europe during the High Middle Ages (between the 11th and 13th centuries). From an economic standpoint, it was a land tenure system that favored the rural nobility and encouraged serfdom. Politically, it entailed a dispersion of power in favor of feudal lords with local and regional authority.

Feudal relationships were contracts of mutual obligations between two freemen: a lord and a vassal. The lord granted protection and land (called "fiefs") to a vassal in exchange for allegiance and military assistance (or other services). Kings had their own vassals who, in turn, could be lords of other vassals, thereby forming a pyramid of land distribution and obligations that involved a significant part of society.

In the feudal system, peasants were particularly important, as the socioeconomic foundation of the system was rural. Serfs, in turn, were tied to land they did not own, and had to pay rents to a lord. Land granted as a fief always included the serfs who worked it. Free peasants were land-owners but could be obliged to pay fees or tribute to a lord with jurisdictional power.

The term "feudalism" is used by some historians to refer to other historical experiences, such as China during the Zhou dynasty, Japan in the shogunate periods, and parts of Eastern Europe at various periods in history.

- See also: Imperialism

Historical context of feudalism

An antecedent to feudalism was the colonate system in the Roman Empire. Under this system, large landowners installed coloni (freed slaves or peasants) on their lands, who had to work them for sustenance and to pay rents to their lord in exchange for protection.

Following the fall of the Roman Empire in the 5th century, Western Europe became divided into several smaller political units. This lasted until the formation of the short-lived Carolingian Empire, which implemented a reward system to loyal nobles, involving land grants in exchange for services (mostly military).

After the fragmentation of the Carolingian Empire in the 9th century, several areas of Western Europe were attacked by Magyars, Muslims, and Vikings. Defense required swift action, which fell upon local lords, who had resources to build fortifications and gather fighting forces without having to wait for the arrival of royal troops.

This encouraged a system of political fragmentation that gave power to feudal lords, and shaped the High Middle Ages. Nevertheless, from the end of the 11th century onwards, some kings, dukes and counts began a process of concentration of political power that placed them in a position of greater authority in their territories, as was the case of King Louis VI of France, Count Ramon Berenguer I of Barcelona, and Duke William II of Normandy, who ascended to the English throne.

The feudal system began to lose prominence in the 14th century, when epidemics, peasant revolts, and the increasing growth of the urban bourgeoisie diminished the power of the nobility and paved the way for the emergence of centralized monarchies.

Feudal society

Social estates

Feudal society was divided into three clearly distinct estates:

- Nobility. Nobles possessed large tracts of land, generally earned as payment for their military efforts or other services (though in practice they could also be inherited). They were organized in lineages and maintained bonds of vassalage with other feudal lords or with the king. According to their nobility titles and their position in the social hierarchy, they could belong to the higher nobility (dukes, counts, and marquises) or the lower nobility (viscounts, barons, knights, and hidalgos, among others).

- Clergy. Ecclesiastical members, whose supreme authority was the Pope based in Rome, handled religious matters, which shaped human behavior at the time. Clergymen could belong to the secular clergy, who resided in churches and cathedrals, or to the regular clergy, who observed the rule of a religious order and resided in convents or monasteries. They often enjoyed the privileges of feudal lords.

- Workers. While in the social hierarchy of the time this estate was composed of serfs, some historians encompass in it various types of workers who would later comprise the so-called "third estate". Serfs were the lowest stratum of feudal society, in charge of working and cultivating the land. Although they were not slaves, they were tied for life to their lord’s land, to whom they had to pay a rent in kind and sometimes other services. Their status was hereditary. Free peasants were land-owners but had to pay tribute or other obligations to the lord, who had jurisdiction over a territory (usually referred to as a "lordship"). Artisans and merchants lived in cities and, although they interacted with other social classes, they remained outside the feudal system.

The Church and the nobles justified this hierarchy by arguing that each estate had a role determined by God: to pray (clergy), to fight (nobility), and to work (serfs and peasants).

The highest authority in a kingdom was the king or emperor, but in practice he also depended on vassalage relationships with other nobles. Feudal lords usually had more real power than the king within the boundaries of their own lands.

Vassalage

One of the most important institutions of feudalism was vassalage. It consisted of a contract of mutual obligations between two free men: the "lord" and the "vassal". Vassalage was a pledge of allegiance and service of the vassal (mainly concerning military matters, though it could also involve a payment) and in return, protection duties or sustenance obligations from the lord.

In this way, the lord granted his vassals "fiefs", i.e. lands (along with the serfs that occupied them) over which the vassals gained usufruct rights. In turn, vassals pledged to assist their lord whenever summoned. Knights were also vassals of a lord (noble or king), but did not always receive a fief in exchange for their service.

Vassalage permeated a large part of feudal society. A king could be lord of a noble vassal to whom he granted a fief, who in turn could be lord of other vassals with similar commitments. The vassalage contract between nobles was formalized with an oath ceremony that included "homage" and "investiture". A vassal who failed to fulfill his oath of fealty incurred a felony and could lose the fief. If a lord failed in his duties, the vassal could break the oath and demand reparation.

In this type of social structure, a feudal lord with numerous vassals could often wield more power than the king himself.

Knights

During feudal times, the figure of the knight emerged, becoming a literary motif in the medieval cantares de gesta and in the 16th-century chivalric novels (parodied in Miguel de Cervantes' famous novel "The Ingenious Gentleman Don Quixote of La Mancha").

Knights were professional mounted warriors at the service of a king or feudal lord. Some received a fief in vassalage. In general, before being knighted they had to complete a series of stages, starting as pages and squires. In addition, they had to acquire their own military equipment (such as sword and armor).

Chivalry was an important military component that provided mobility and attack strength, but which also became an ideal of honor and religious devotion. Knights had to adhere to a strict code of conduct. Their participation in the Crusades was of major importance, and some Catholic religious-military orders, such as the Knights Templar and the Teutonic Knights, arose from these military campaigns.

The Catholic Church

One of the most significant events of the 11th century was the schism that broke the Western Catholic Church from the Eastern Orthodox Church (1054). Furthermore, in those years the Catholic Church underwent a series of reforms spurred by criticisms to corruption and practices such as the sale of ecclesiastical offices and the conferring of lay investiture (in accordance with the principles of vassalage but contrary to the doctrine of the Church).

Some of these reform movements originated in monasteries like in Cluny in France. The dispute over the appointment of clergymen (including the Pope himself) pitted the Church against the Holy Roman Empire during the so-called "Investiture Controversy" (between 1075 and 1122). Eventually, an agreement was reached by which the laity could neither invest clerics nor select the Supreme Pontiff, but rather he would be elected by a college of cardinals. This ensured papal supremacy in religious matters.

In feudal society, ecclesiastics (mainly bishops and abbots) enjoyed the privileges that their position afforded them in the feudal hierarchy: they owned lands and exploited serfs. But they also provided an ideological justification for the system. According to the Catholic Church, kings ruled by the grace of God, and the prevailing rigid social order, which caused all sorts of suffering to those who did not belong to the privileged estates, emanated from God and should not be questioned.

One of the most important enterprises of the Catholic Church in feudal times was the launch of the Crusades. The first of these military expeditions to the Holy Land arose from a call made by Pope Urban II to all of Christendom (which included the realms and nobles of Western Christianity in agreement with the Byzantine Empire) to expel the Seljuk Turkish Empire from the "Holy Land".

Only the first of these Crusades was successful for Christendom, but it nonetheless had major consequences, such as the creation of religious-military orders, the strengthening of religious fervor, and the opening of trade routes across the Mediterranean. The defeats in the subsequent Crusades had adverse effects on the Church and other privileged classes.

Rural economy

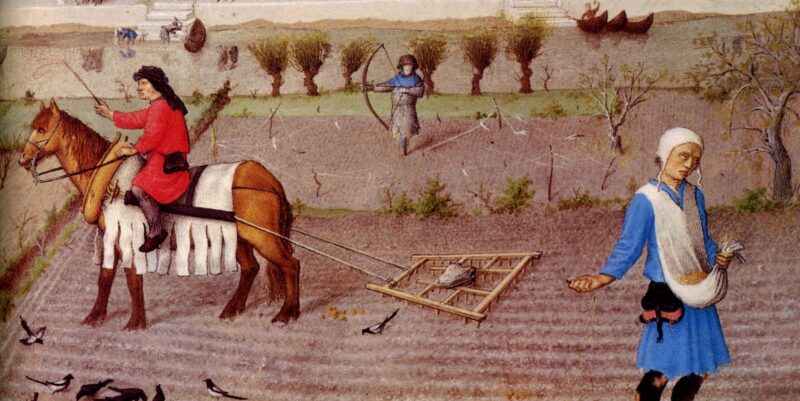

In feudal times, the generation of wealth essentially stemmed from agriculture and cattle raising, carried out by serfs and free peasants.

This rural economy experienced growth between the 11th and 13th centuries due to the expansion of arable lands as a result of plowing and triennial rotation, particularly in France, England, Germany, and the Low Countries. Also important were improvements in the plow and the use of mills.

Rents and tributes

The feudal economy was grounded in rents and tribute. Serfs had to pay "in kind" (grains, livestock, or other agricultural products) for the right to live on the lord's land. In some cases, they were also required to fulfill labor duties, such as providing hand labor (for example, in the lord's demesne).

Free peasants also had to pay rents or tribute, generally in kind. The “banal lordship” granted some lords jurisdictional power over a territory where they could administer justice and levy taxes for the use of bridges, ovens, mills, or other facilities under their charge. Another form of tribute was tithing, originally a 10% contribution of the produce destined to the maintenance of the clergy.

Cities and trade

In the early years of feudal society trade was very limited, and the characteristic urbanism of the Roman Empire had been replaced by a nearly absolute ruralization of the economy (with the exception of a few Italian cities). However, cities and trade experienced a resurgence beginning in the late 11th century.

Agricultural innovations facilitated the generation of larger surplus, which was used for the purchase of handcrafted products, such as fabrics or new tools. These, in turn, improved production and increased agricultural surplus, thus allowing the cycle to expand.

These transactions were usually conducted in "burgs" or towns inhabited by artisans and merchants (known as "burghers"). They were often located near castles or at crossroads and were typically fortified. These cities housed markets that were often under the protection of lords. The commercial trade stimulus made it possible to hold seasonal trade fairs involving exchanges on a larger scale. Currency increasingly began to circulate in these fairs and, in time, some merchants and artisans began to offer loans, becoming the earliest bankers and financiers.

City dwellers organized themselves in merchant and craft guilds by trade and enjoyed growing autonomy from feudal lords. They obtained privileges and other liberties guaranteed by the king, and in some cities they even came to establish autonomous governments with their own municipal ordinances. The wealthier sectors formed urban patriciates, but sometimes had to face conflicts with feudal lords, which partly explains the use of defensive walls and the subsequent formation of leagues or confederations of cities.

Many cities played a major role in long-distance trade routes. The most prominent cities were those situated in Northern Italy, where merchants competed for the control of Mediterranean trade. Pilgrimage routes and the Crusades also became important trade routes.

Military system

The feudal order emerged following the fragmentation of the Carolingian Empire and the onslaughts from Vikings, Magyars, and Muslims. The lords who offered military protection, provided by the service of vassals and the construction of castles, accumulated great power. This military system played a significant role during the frequent wars between kingdoms or lords, which were raids and sieges rather than pitched battles.

This type of warfare emphasized the significance of siege engines and cavalry mobility. Knights were important in the Crusades that pitted Christian combatants against Muslim armies for the control of the Holy Land.

In feudal times, warfare served as a means to settle dynastic or territorial disputes, enabling the victors to reap economic benefits by seizing the lands of the vanquished, thereby increasing their pool of serfs (who were tied to the land), and thus enhancing their capacity to produce food and acquire new vassals.

However, warfare could also be a source of discontent among peasants, who saw their lands frequently plundered or were subjected to increased tributes to fund the wars of nobles or kings. This might have explained some of the peasant revolts in the 14th century.

Castles

One of the most notable features of the Middle Ages were castles. Throughout the feudal era, numerous fortified structures were erected across Europe, usually situated in strategic locations, such as on high ground. Commissioned by kings or feudal lords, these structures primarily had defensive functions and served as bases for military operations.

In the event of enemy assault, their towering stone walls provided protection for the lord (known as "castellan") and his family, and refuge to the peasants within his manor. In addition, they ensured supplies during sieges.

Some of these structures were begun amidst the intermittent attacks from Vikings, Magyars, and Muslims during the 9th and 10th centuries. Over time, construction techniques evolved and refined.

Castles were often concentric, that is, they had a double wall (outer and inner), and had one or more towers, interior courtyards and, sometimes, a peripheral moat. In addition to their defensive function, castles served as the permanent or temporary residence of the lord, who often received his vassals there. Castles were also inhabited by men-at-arms and servants.

During the Crusades, castles were built in Asian territory, such as the imposing Krak Des Chevaliers in present-day Syria.

End of feudalism

The decline of feudalism in Western Europe during the 14th century was brought about by various factors. Wars, epidemics, and urban migrations reduced the rural population. The subsequent labor shortage accelerated the end of serfdom. Nobles, who had to face important peasant revolts, gradually started to lose political power.

In wars (notably within the context of the Hundred Years' War), kings began to rely more on mercenaries than on their vassals, with the latter paying their obligations with currency. Lords progressively abandoned their manors, and leased their lands to peasants instead.

The urban bourgeoisie accumulated wealth, becoming moneylenders to kings and princes. This consolidated great commercial houses that served the increasingly centralized monarchies in a growing monetized economy.

Finally, while certain aspects of feudal society lingered for centuries, the power of lords inevitably declined.

Explore next:

References

- Bloch, M. (1986). La sociedad feudal. Akal.

- Brown, E. A. R. (2021). feudalism. Encyclopedia Britannica.

- Duby, G. (1992). Los tres órdenes o lo imaginario del feudalismo. Taurus.

- García de Cortázar, J. A. & Sesma Muñoz, J. A. (2008). Manual de Historia Medieval. Alianza.

- Le Goff, J. (1999). La civilización del occidente medieval. Paidós.

Was this information useful to you?

Yes NoThank you for visiting us :)