We explore medieval culture, and describe its characteristics. In addition, we discuss medieval society, politics, and art.

What is medieval culture?

Medieval culture is understood as the set of social, political, economic, and cultural manifestations that characterized the historical period known as the Middle Ages or medieval period in Europe.

This period spanned from the 5th to the 15th centuries, and was traditionally considered a time of obscurantism and cultural decline, a transition era between the splendor of the preceding Greco-Roman antiquity and the Renaissance of classical Western culture that followed.

Today, medieval culture is regarded as a much more complex phenomenon which, despite being marked by the strict religious control of Christian institutions as well as significant levels of poverty (especially in rural areas), inequality, and illiteracy, it also gave rise to a variety of cultural and artistic manifestations.

- See also: History

Characteristics of medieval culture

- Medieval culture developed in Europe between the 5th and 15th centuries. While it was traditionally viewed as a dark and decadent era, it is now recognized as a far more complex and diverse phenomenon.

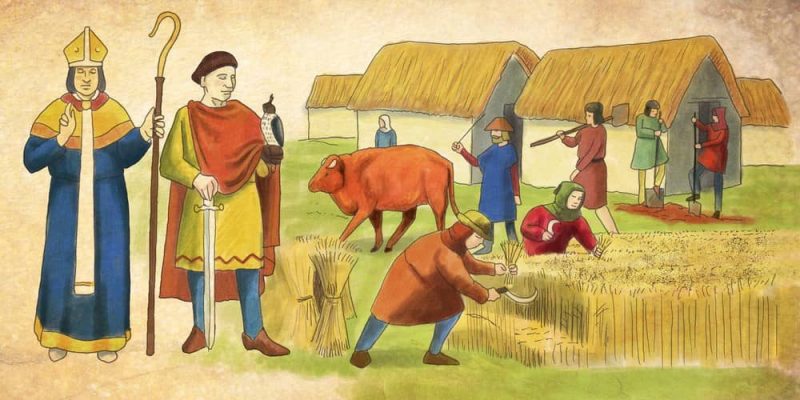

- Medieval culture was mainly rural, emerging in agricultural lands controlled by feudal lords bound by ties of vassalage to other lords or a king.

- The clergy and nobility were the upper classes in society, having their own codes of conduct. Serfs and peasants worked the lands and had their own customs.

- Medieval culture saw a resurgence of urban life and the rise of merchant bourgeoisies, who expanded trade across the Mediterranean.

- The Middle Ages witnessed a number of philosophical, technical, and scientific advances, albeit under the watchful eye of the Church and the Inquisition.

- Religion and the Church were at the heart of medieval culture, which was dominated by a theocentric worldview that legitimized social inequalities.

- While medieval art was heavily influenced by religion, it nonetheless gave rise to major styles like Romanesque and Gothic.

Historical context

The Middle Ages was a long period spanning nearly a thousand years, beginning with the fall of the Western Roman Empire caused by migrations and invasions in the 5th century and ending with the fall of Constantinople to Ottoman forces in 1453.

It is usually divided into three subperiods:

- Early Middle Ages (5th to 10th centuries)

- High Middle Ages (11th to 13th centuries)

- Late Middle Ages (14th to 15th centuries)

While these periods shared common characteristics throughout Europe, they were also marked by significant differences. For this reason, descriptions of medieval culture should be considered broadly.

Medieval society

During much of the Middle Ages in Western Europe, society was organized under a feudal system of land tenure and vassalage. Land was owned by "feudal lords" (kings or nobles), who granted portions of it (known as "fiefs") to their vassals in exchange for loyalty and military services. These lands were typically worked by peasants bound by ties of servitude. This system is known as feudalism.

Society was predominantly rural, being ideologically supported by the Church (whose clergy could also be feudal lords). Religious ideology asserted that the division of medieval society into three estates was determined by God: the clergy's role was to pray, that of the nobility was to fight while the peasants and other lower classes in farms and cities had to work.

Medieval society generally hindered social mobility. However, during certain periods of the Middle Ages, some lower nobility classes could aspire to greater wealth. Furthermore, the 14th-century crisis caused the emancipation of serfs and improved working conditions for peasants. In addition, the growth of cities from the High Middle Ages onward resulted in a prosperous mercantile bourgeoisie and the expansion of trade across the Mediterranean.

Political fragmentation and cultural diversity

Western Europe was marked by political fragmentation throughout much of the Middle Ages. Kings often wielded less real power than their vassals, who acted as feudal lords with authority over lands, serfs, and peasants. External invasions and conflicts among feudal lords prompted the construction of walls and castles, which further emphasized these divisions.

In addition to political fragmentation, there was cultural diversity, shaped by the different lifestyles across Europe. Migrations became a characteristic feature after the fall of the Western Roman Empire. As a result, Christian Europe comprised various populations: Hispania people, Visigoths, Romans, Britons, Normans, Anglo-Saxons, Franks, and Lombards, among others.

Despite the differences, Christianity and the recognition of papal authority (though not without tensions and conflicts with nobles and kings) gave Christendom a common sense of identity. This unity was further strengthened during the Crusades, as opposed to Islamic populations and those deemed pagan.

The Church and theocentrism

The Middle Ages was a period characterized by theocentrism. Kingdoms and nobles in Western Europe saw themselves as part of a unified Christendom under the authority of the Pope, though conflicts were not uncommon. In theory, kings were subject to the Pope’s authority and could be anointed by ecclesiastical authorities, but in practice, tensions often arose between monarchs and emperors and the pontiff.

Religious identity was intensified by the "Reconquista" in the Iberian Peninsula and the Crusades, which reinforced the divide between the Christian West and the Muslim, pagan East. These events also gave rise to military monastic orders, such as the Knights Templar, as well as monastic and mendicant orders.

The Catholic Church's doctrine exerted a decisive influence on the customs, traditions, and laws of medieval society. The Inquisition was in charge of investigating and condemning cases of alleged heresy (deviation from Catholic orthodoxy), with secular authorities carrying out punishments.

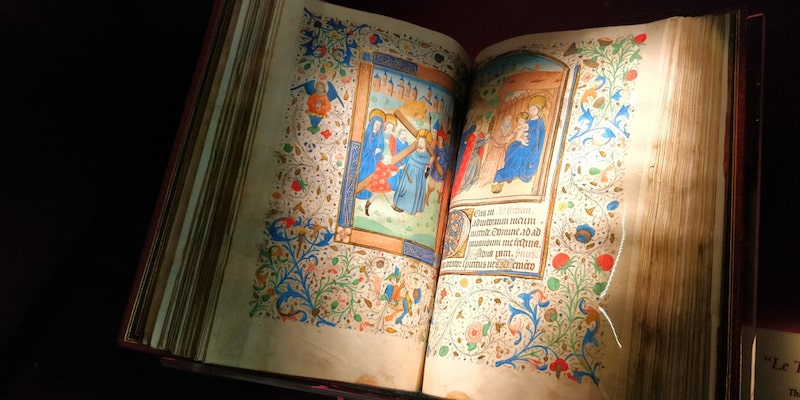

The theocentrism promoted by the Church was reflected in both art and thought. Scholasticism, taught in universities, subordinated reason to faith, holding the idea that God was the measure of all things. Visual arts often depicted Christian themes to convey the Church's teachings.

Medieval art

Art in the Middle Ages was heavily influenced by Christian religion, being both supported and dominated by the Church. Medieval art is usually classified into three periods or styles:

- Pre-Romanesque (5th to 10th centuries)

- Romanesque (11th to 12th centuries)

- Gothic (12th to 16th centuries)

Each of these styles had distinct characteristics, which in turn rendered them different from classical Greco-Roman and Renaissance art, in architecture as well as in painting and sculpture. Unlike the Renaissance, when patrons were private individuals, art in the Middle Ages was predominantly subordinate to the Church.

Since most of medieval society was illiterate, literary works were produced by clergymen. As a result, the prevailing literature was hagiographies (the lives of saints), theological or Christian philosophical reflections, and mystical poetry.

Nevertheless, epic songs and chivalric tales, such as the chansons de geste, were also composed. They centered on heroic figures like El Cid Campeador (who had fought against the Moors in the Iberian Peninsula) or Roland (a Frankish commander during the Carolingian Empire), and always conveyed Christian symbolism.

A large number of pagan popular narratives and songs were banned and replaced with "correct" Christianized versions. In some cases, this merely involved cloaking Celtic and Germanic tales in a Catholic veneer. In this way, many oral traditions of non-Christian European peoples have survived to this day. Another notable literary form was the bestiary, which described real and mythical creatures in religiously tinged terms, thus blending fantasy and imagination.

Popular culture in the Middle Ages

The lower classes engaged in festivities, games, and dances in which the body and the grotesque were given loose rein. These activities differed from both the religious festivities held by the Church and the secular festivities of the aristocracy.

Carnival, in particular, has been interpreted by some historians as a form of resistance against ecclesiastical oppression and the dominance and refinement of the upper classes. Other popular celebrations held religious meanings tied to village life, such as births and weddings.

Troubadours and wandering minstrels were a prominent feature of medieval popular culture, traveling from village to village, performing romances and poetry often rooted in folk traditions and imaginary far removed from Christian rigor. Over time, some of these traditions were incorporated into literary works that adapted them to the official religious beliefs.

Medieval science

Although the scientific method is a product of Renaissance humanism, the Middle Ages was not devoid of scientific and technological innovations. Some of these developments had practical purposes, such as increasing agricultural productivity, improving military performance, and advancing navigation. However, innovations were often subject to the scrutiny of the Church and the Inquisition, which could lead to accusations of witchcraft or heresy.

Certain technical advancements were introduced by the Arabs and the Byzantines, including the manufacture of gunpowder, which had first been developed in China.

The figure of the alchemist, who during the Middle Ages gained reputation as a sorcerer capable of manipulating the elements and revealing the arcane secrets of nature, seems to have been influenced by Arab traditions. Alchemy contributed to the subsequent development of experimental methods, particularly in chemistry (alchemist Roger Bacon presumably introduced gunpowder to Europe). Similarly, theologians like William of Ockham laid the groundwork for what later became the scientific method.

Universities rose during the Middle Ages as centers for the study of theology. They were often linked to philosophical ideas such as those of Aristotle, which they adapted to the Christian doctrine—a process exemplified by thinkers like Thomas Aquinas. These institutions also taught law, rhetoric, medicine, arithmetic, geometry, and astronomy. Nevertheless, religious dogma imposed limitations, restricting conclusions such as the idea that Earth was not the center of the universe.

Medieval Latin

Latin, which had spread across Europe during the Roman Empire, survived as the scholarly language of the Middle Ages. It served as lingua franca for communication among royal courts, teaching in universities, and writing in the Christian kingdoms of Western Europe, unlike Greek, which was used in the Byzantine Empire and the Eastern Church. Latin also gave rise to the Romance languages including Spanish, Italian, French, and Portuguese.

From the 14th century onward, vernacular languages increasingly appeared in written works, but Latin remained in use until at least the late Early Modern period. Today, the Catholic Church continues to use Latin in certain liturgical contexts, though its use ceased to be mandatory following the Second Vatican Council in 1962.

Explore next:

References

- "Historia universal de la Edad Media" Akal. Álvarez Palenzuela, V. A. (coord.) (2002).

- "Manual de historia medieval" Alianza. García de Cortázar, J. A. & Sesma Muñoz, J. A. (2014).

- "Middle Ages" Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia (2022) in https://www.britannica.com/.

Was this information useful to you?

Yes NoThank you for visiting us :)