We explain what Athenian democracy was, its origin, and how it worked. In addition, we discuss its characteristics and importance.

What was Athenian democracy?

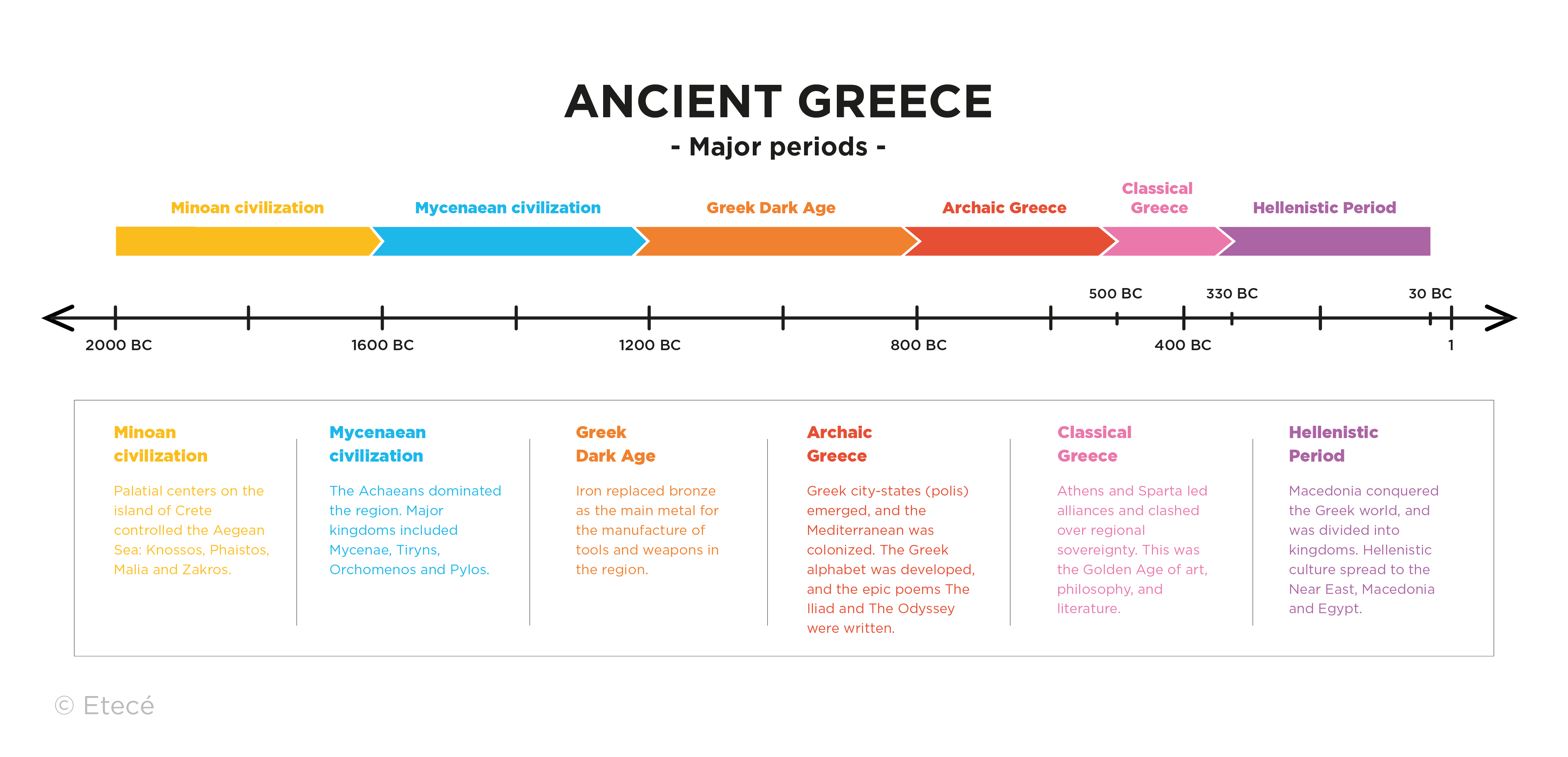

Athenian democracy was the form of government established in the city-state of Athens, in Ancient Greece, between the 6th and 4th centuries BC.

It stands as the earliest democracy in human history and served as a decisive precedent for democracies in Western countries from the 18th century AD onwards.

Athenian democracy is regarded as a direct democracy, one of the few in human history, in which the legislative and executive power was exercised directly by the people, rather than by representatives acting on their behalf.

The Athenian democratic system was based on popular sovereignty. Through its institutions, it encouraged the political participation of its citizens in different aspects of public life.

- See also: Ancient Egypt

Geographical and temporal setting of Athenian democracy

Athens was a Greek polis (city-state) comprising the entire region of Attica in southern Greece, on the shores of the Aegean Sea.

Around 508 BC, after two centuries of monarchy, Athens implemented democracy as a form of government. This period, known as Classical Greece, covers from the zenith of Greek culture to the conquest of the region by Alexander the Great’s Macedonian Empire and the subsequent suppression of democratic institutions in 322 BC.

History of Athenian democracy

Background

The Athenians were the inhabitants of the city-state of Athens, one of the most important in ancient Greece. Their form of government was originally a monarchy, whose power was limited by the Areopagus (Council of Landowners). Towards the 7th century BC, an aristocratic group known as the Eupatridae abolished the monarchy and established an oligarchy. From then on, the Areopagus elected three archons in charge of the government's executive functions. However, this concentration of power bred discontent among Athenians.

From the end of the century and throughout the following, archons like Draco of Thessaly and Solon of Athens introduced several reforms that weakened the privileges of the Eupatridae, favoring the wider population. Between 561 and 510 BC, Pisistratus seized power and established a tyranny (government based on the use of force). During his rule, Pisistratus took measures that received great popular support.

Establishment of democracy

Following the death of Pisistratus, power struggles ensued among the various factions until the group led by Cleisthenes overpowered the rest. Around 508 BC, Cleisthenes introduced a series of reforms that fostered collective responsibility in decision making and promoted equality before the law.

In 465 BC, Ephialtes continued the reforms to develop democratic institutions and, eventually, Pericles finished shaping the Athenian democratic system.

The democratic period coincides with the zenith of Athens in the regional context. The 5th century BC is known as the Golden Age, due to the cultural, political and economic splendor of Athens, and its military supremacy over other Greek cities. Ephialtes and Pericles drove reforms aimed to develop democratic institutions in the city and give the Athenian people real and effective access to power.

Crisis of Athenian power

In the second half of the century, the political rivalry between Athens and Sparta began to affect the rest of the Greek cities. The Delian League, led by Athens, and the Peloponnesian League, led by Sparta with the support of the Persians, were formed. In 404 BC, the Athenians were defeated.

The cost of the war further weakened the polis, allowing the advance of the Macedonian people who, in 334 BC, imposed themselves upon the Greek. Finally, in 322 BC, under Macedonian control, democracy was suppressed, and with it, all the democratic laws and institutions of Athens.

Society in Athenian democracy

Although this period of Athenian history saw the political participation of the demos (Greek word for "people"), Athenian society was nonetheless marked by inequality. The definition of citizenship excluded women, foreigners, and slaves. Only men over the age of 20 born to Athenian parents were considered citizens.

Women were regarded as subordinate subjects to men's decisions and lacking the necessary independence to act on their own initiative.

Metics were foreigners, born in other Greek cities and residing in Athens. They were neither considered citizens nor were they authorized to own land. They engaged in commerce or the manufacture of handcrafted goods.

Slaves constituted one third of the Athenian population. They had no freedom, no political rights, and were regarded as the private property of their owners. They were mainly employed as domestic servants, for handcraft production, and as labor in agriculture.

Political organization of Athenian democracy

Athenians developed a complex democratic system, in which various institutions and magistrates were responsible for the tasks of the different branches of government.

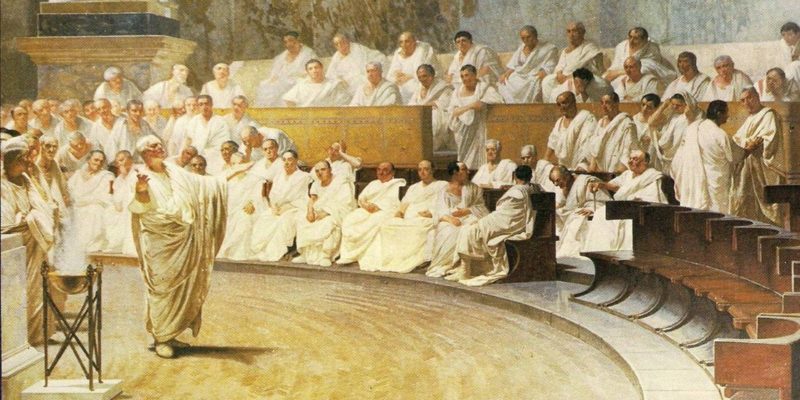

Sovereignty was popular, meaning that power belonged to the demos (Greek word for "people"), and was exercised through the Ecclesia (Popular Assembly). The Athenians sought that participation of citizens be obligatory regarding decision making and the drafting of laws. They believed that in this way equal political rights were guaranteed.

To this end, a system was designed wherein citizens performed governmental functions through magistrates and institutions, thereby ensuring the enforcement of laws and rules introduced by popular sovereignty.

The legislative power was held by the Council of Five Hundred (also known as the Boule), composed of 500 citizens, representatives of the 10 tribes of Attica (50 per tribe). The judicial power was organized on the basis of popular courts supervised by the Heliaia (supreme court) and the Areopagus (council of elders).

The tasks of the executive power were divided among several magistrates. This structure prevented the concentration of power in the hands of a few. The tenure of official positions was limited in time and to a single term, with some specific exceptions.

Government institutions

Two institutions were the cornerstone of popular sovereignty in Athenian democracy:

- Ecclesia: Assembly of the citizens. It was comprised of up to 6,000 people, who attended meetings freely. This assembly was charged with the most important decisions, such as legislating, appointing officials, judging crimes and offenses, and carrying out executive decisions (like waging war or granting citizenship to foreigners). The assembly met periodically, usually four times every 36 days. As the democratic model became more complex, certain magistracies were designated to perform some judicial and legislative functions.

- Boule: the Council of Five Hundred. It was a restricted assembly whose members were in charge of the daily affairs of the city. It was comprised of 500 representatives elected from each of the Athenian jurisdictions. Starting with Pericles, assembly members received a special pay in exchange for performing deliberative, administrative, and judicial functions, overseeing other institutions, and ensuring the system's operation.

Another important institution was Heliaia, the supreme court for justice matters. It was composed of 6,000 citizens who received the name of dikastes ("those who have sworn") or heliasts.

The Heliaia was elected by lot among 6,000 citizens over 30 years of age who had voluntarily applied. It was a paid office. Chosen members had to take an oath, and were in charge of decisions regarding public (graphe) and private (dike) trials.

Magistrates

Athenian democracy had magistrates (public officials) who were in charge of the executive tasks of government. They performed military, administrative, religious, and judicial functions, and supported the assemblies.

Most positions were filled by citizens chosen by lot, who could hold office only for a single term and for a limited period. In contrast, there were specific magistrates in the Assembly elected by vote, who could be reelected in the same manner.

The most important magistrates were:

- Archons (Eponymous Archon, Polemarch, Archon basileus or “king” archon, and Thesmothetai). They fulfilled executive functions, and were controlled by a committee of the Council of Five Hundred. Upon retirement, they became members of the Areopagus (council of elders).

- Magistrates of civil administration (market inspectors, fund administrators, and other magistrates). There were over 600 individuals who voluntarily applied and were chosen by lot. They were involved in the administrative tasks of the government.

- Magistrates of military administration (strategos, taxiarchs, phylarchs, hippeis, and military treasurer). These officials were directly selected by the popular assembly ("Ecclesia").

During the 5th century BC, Pericles instituted the remuneration of magistrates, since he believed they provided a service to the citizenry. In this way, people with no time or resources for political participation were brought to public life.

Magistrates were chosen in two different ways:

- Offices by lot. This was the most common method for appointing public officials, as it was considered the most democratic: all citizens were to govern and be governed in turn. Thus, no advantage or merit was taken into account in the election.

- Offices by ballot. Around one hundred officials out of a thousand were elected by public vote: treasurers and officials responsible for managing large amounts of public money, and the strategoi, generals elected from among the prominent members of the polis. They were audited before and after holding office to prevent corruption.

Importance of Athenian democracy

Athenian democracy represents a major milestone in the political history of the world, being the first democracy of which there is extensive record.

It is the source of ancient legal texts, which later served as the basis for legal legislators of the Roman Republic. Its influence extended to subsequent Western civilizations, including the French.

Difference with present-day democracy

When compared to Athenian democracy, modern democracies function indirectly, as they are representative rather than direct democracies.

- Representative democracy (present-day). The people elect officials who represent them politically, making decisions on their behalf based on partisan political guidelines.

- Direct democracy (Athenian). The Athenian citizens participated directly, that is, they themselves made decisions and voted either in favor or against, without representatives.

Explore next:

References

- “Democracia ateniense”. Wikipedia.

- “Antigua Grecia – La democracia ateniense” (video). Educantina.

- “La democracia ateniense”. ArteHistoria.

- “El funcionamiento de la democracia ateniense”. Historia General.

- “Athenian Democracy”. Ancient History Encyclopedia.

Was this information useful to you?

Yes NoThank you for visiting us :)