We discuss the life of Pablo Escobar and his initiation into crime. In addition, we explain why he is considered one of the greatest criminals in history.

Who was Pablo Escobar?

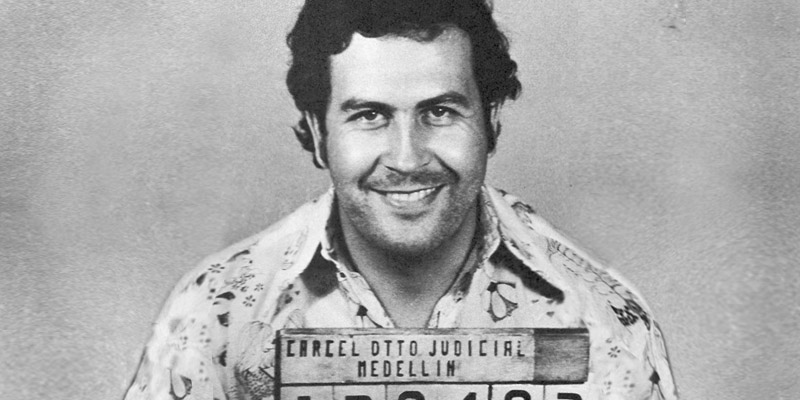

Pablo Escobar was a Colombian criminal and drug trafficker, founder and leader of the criminal organization known as the Medellín Cartel. Dubbed the "King of Cocaine", in his short lifespan of just 44 years, he was the world's leading drug trafficker during the 1980s, managing to amass a fortune estimated at 30 billion dollars.

At the height of his criminal empire, Escobar led an extravagant lifestyle, owning a 2,800-hectare estate called "Hacienda Nápoles" ("Naples Estate" in Spanish), on which he had artificial lakes, a landing strip, a zoo, a bullring, and life-sized dinosaur statues.

He also established various philanthropic and social assistance organizations that earned him a Robin Hood-like image, so much so that he managed to secure a seat in the nation's congress in 1982.

However, Escobar's infamous ruthlessness was widely widespread among his acquaintances and collaborators: he was known for solving problems with "plata o plomo" (literally "silver or lead", meaning money or death). In 1989, he was the mastermind behind the bombing of an airplane, which killed around 100 people.

Killed by the police in 1993, his figure has become part of contemporary urban mythology and has been a source of inspiration for literature works and film.

- See also: Fidel Castro

Early life of Pablo Escobar

Pablo Emilio Escobar Gaviria was born on December 1, 1949, in the town of Rionegro, in the Colombian state of Antioquia. He was the second of seven children of a humble household born to farmer Abel de Jesús Escobar Echeverri and schoolteacher Hermilda de los Dolores Gaviria Berrío.

Shortly after Pablo's birth, the family moved to Envigado, in the suburbs of Medellín, Colombia's second largest city. There, Pablo grew up and soon his leadership skills and his knack for business became evident: together with his cousin Gustavo Gaviria, they organized raffles, traded magazines, and made low-interest money loans.

Eventually, Pablo was elected as president of the Student Welfare Council, managing to gain access to school information, such as exams. Teachers recall him as a quiet boy, obsessed with his appearance and with a complex about his height. During this period, Pablo came into contact with the revolutionary left. Many of his former peers took up armed struggle. According to them, Pablo sympathized with the leftist imaginary, while at the same time he dreamed of amassing a true fortune.

In 1969, he completed his high school education at the Lucrecio Jaramillo Vélez high school and was admitted to the Economics program at the Universidad Autónoma Latinoamericana of Medellín. However, he soon lost interest in university studies and preferred to engage in illicit businesses. He would allegedly have sworn to commit suicide if he did not have a million pesos at his disposal by the age of 25.

Beginnings in the drug trafficking

Since he moved to Medellín, Pablo had been in contact with other young people from the poorest neighborhoods. Among them were the sons of the wealthy Henao family: Mario, Carlos and Fernando, and his own cousin Gustavo. As teenagers, Pablo, Mario and Gustavo became friends and partners in crime, including the forgery of diplomas, the smuggling of sound equipment, and the theft of aluminum tombstones.

This trio of young criminals attracted the attention of local organized gangs, among them that of Diego Echavarría Misas, a famous smuggler, and later Alfredo Gámez López, dubbed the "Padrino" (the "Godfather"), the country's leading smuggler. By then, Pablo and his accomplices had already become skilled car thieves.

Initially acting as bodyguards and hit men, soon the "Godfather" Gámez López sent them on a trip to buy coca paste in Peru and Ecuador, for later processing in Colombia. This was how they entered drug trafficking. Those were the years of the "Marimba Bonanza", and thousands of dollars were flowing into Colombia from the export of marijuana to the US.

Around that time, they also became acquainted with smugglers Elkin Correa and Jorge Gonzalez. From them, Pablo learned the smuggling routes and established important connections in the drug world, which would later prove very useful in founding the Medellín Cartel. Pablo's steely resolve, his ruthless personality, and the fact that he did not consume cocaine made him very popular within the organization.

On June 9, 1976, Pablo and Gustavo were arrested for the first time near Medellín, transporting a shipment of 20 kilograms of cocaine hidden in the wheels of their car. They were released after a few months in prison.

The "bonanza marimbera" ("marimba bonanza") was the name given to the influx of millions of dollars from drug trafficking into Colombia between 1974 and 1985 from the illegal export of marijuana to the United States. This "bonanza" proved of great importance for the growth of local drug cartels, ending in the mid-1980s, when marijuana cultivation in Colombia was largely replaced by cocaine.

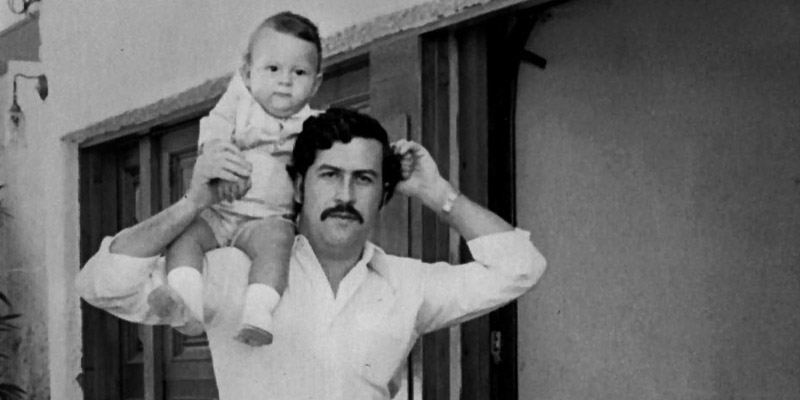

Marriage to "La Tata"

At the age of 24, Pablo met Victoria Henao Vallejo, a sister of his associate Mario, and declared his love for her. At that time, the young woman was 13 years old. Despite her family's opposition, Pablo and Victoria got married two years later. In 1977, Juan Pablo was born, and in 1984, Manuela. The couple remained together until Pablo's death.

Following Pablo's death, Victoria and her children had to flee Colombia. Since almost no country accepted them, they emigrated to Mozambique, where they lived in very harsh conditions.

Eventually, they legally changed their names and emigrated to Buenos Aires, where they were victims of extortion by an accountant who knew their real identities. They were imprisoned, being released eighteen months later, thanks to the mediation of Nobel Peace Prize winner Adolfo Pérez Esquivel.

Shortly after Pablo's marriage, "Padrino" Gámez López was denounced and investigated by the Colombian state, and ended up in jail on two occasions. His contacts in politics, however, helped him serve just one year in prison before retiring to the Caribbean city of Cartagena.

From then on, many minor players were in charge of the drug business. In 1977, they all came together in a single organization, which in 1982 was given the name of the cartel de Medellín (Medellín Cartel). Pablo Escobar was among its founders and became the head of the organization, which was responsible for the production, distribution, and sale of 80% of the cocaine consumed in the United States.

Medellín Cartel

Since its origin, the Medellín Cartel had a hierarchical and well-organized structure, which allowed its associates to share resources, carry out operations, and yet maintain their production centers and business separate.

"Medellín Cartel" was named by the United States Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), since it was based in the city of Medellín. The cartel's boom took place in the 1980s, as cocaine consumption took hold in the United States, with Colombia becoming its major supplier.

To establish its dominance, the cartel resorted to murder, corruption, and bribery. Escobar, at the head of this criminal organization, imposed the so-called "silver or lead law", according to which the cartel offered government officials money in exchange for their favors, or else their lives and their families were under threat if they refused the bribe.

Eventually, the cartel resorted to terrorism and armed confrontation, both with state forces and with the rival cartel, based in Cali. This sparked a bloody "cartel war" that lasted from 1986 to 1993.

The "Cali Cartel," so named by the DEA, was led by brothers Gilberto and Miguel Rodriguez Orejuela, as well as José Santacruz Londoño and Hélmer Herrera Buitrago. It was also known as "The Cocaine Inc.", "The lords of Cali", or "The Cali KGB".

Pablo Escobar and politics

By the age of 29, Pablo Escobar had already amassed a considerable fortune. He was dubbed "El Patrón" (The Boss) by members of the cartel. It was then that he decided it was time to have a front, or as he called it, "a screen," which would allow him to appear openly in public. And so it was that Pablo Escobar entered the world of politics.

Presenting himself as a philanthropist, he began to show himself publicly with lawyers, financiers, politicians, and to cultivate an image of a successful man. He soon began the construction of facilities intended for the lower classes of Medellín, such as sports stadiums and even an entire neighborhood called "Medellín sin tugurios" (Medellín without slums), which later became known as "Barrio Escobar". These types of actions earned him the affection of the popular classes, while also the accusation of populism.

At the same time, Escobar embarked on a life of excess and eccentricities. He invested 62 million dollars to buy and develop a plot of land in Puerto Triunfo, 112 miles (180 km) from Medellín. There, he established his luxurious "Hacienda Nápoles", which featured a private landing strip and a hangar for airplanes, motorcycles, vans and other vehicles, a gas station, a bullring, a stable, a medical center, dinosaur statues, and a zoo with exotic animals like camels, elephants, rhinoceroses, moose, and hippos.

"Nápoles" was open to visitors during the weekend, as Escobar considered that it also belonged to the Colombian people. The estate also hosted large celebrations.

Through corruption, extortion and hired killings, Escobar managed to gain a significant amount of political, economic, military, and even religious influence, as despite his criminal record, he never ceased to be a devout Catholic.

In this way, Escobar managed to register in the Nuevo Liberalismo (New Liberalism) party, from which he was later expelled. Later, he managed to get himself elected, through various ruses, as an alternate senator to the Senate for Alternativa Liberal (Liberal Alternative movement) in the 1982 parliamentary elections.

However, Escobar's "screen" began to fracture around 1983 when investigations into his fortune began under Justice Minister Rodrigo Lara Bonilla (1946-1984), who was part of the Belisario Betancur administration. The investigation of dirty money in Colombian soccer and politics, as well as the reopening of old legal cases against Escobar, allowed Lara to seize planes and properties used in drug trafficking, and to expose jungle labs dedicated to cocaine production. Thus, not only was Escobar's election to parliament questioned, but the origin of the money that financed him was exposed, and the truth was spread by the El Espectador newspaper.

Escobar and his allies attempted to tarnish the minister's reputation by fabricating evidence incriminating him in corruption, but to little avail. In the end, on April 30, 1984, Lara Bonilla was gunned down by Escobar's hit men as he was driving through the streets of Bogotá. This assassination prompted the president to pass an Extradition Law to the United States and declare martial law, which marked the beginning of the war against narcoterrorism in Colombia.

War against narcoterrorism

By 1984, Escobar's political career was over. The revelations in El Espectador had cost him his seat in parliament and his US visa, prompting him to retire from public life. Shortly after, arrest warrants were issued for the leaders of the Medellín Cartel, and Escobar was forced into hiding.

That same year, police forces, in conjunction with the US DEA, discovered and raided a complex of cocaine processing laboratories near the Yari River, known as Tranquilandia. It was a major blow to Escobar's operations, and the cartel responded by unleashing a wave of terror: car bombs, assassinated journalists, and shot judges became daily news.

Many politicians and officials, bought or threatened by Escobar, allowed the organization to act with impunity, even though its leaders, then dubbed "los extraditables" (the extraditable ones), were already publicly known. At the same time, the Medellín Cartel secured international allies. They already had the support of similar organizations in Mexico, Honduras, Nicaragua, and Cuba.

Until then, Escobar and his allies controlled 90% of Colombia's drug trade but had good relations with rival cartels. However, after the assassination of Minister Lara, a crime the Cali Cartel considered counterproductive, starting in 1986 tensions between the two cartels led to a new escalation of violence: the cartel war.

War between cartels

The break between the two major Colombian drug cartels occurred under circumstances that remain unknown. According to Jhon Jairo Velásquez "Popeye," one of the most notorious hit men for the Medellín Cartel, tensions flared when one of Escobar's most loyal men asked him to carry out a personal vendetta against a member of the Cali Cartel, known as "Piña."

"Piña" was protected by Helmer "Pacho" Herrera, the fourth in command of the Cali Cartel, who did not take kindly to Escobar's request to hand over his subordinate. When Escobar's request was ignored, the boss ordered the kidnapping and execution of "Piña," triggering the break between the two organizations.

In addition to fighting each other, the cartels contributed to the capture of rival leaders at the hands of the police. In this context, in 1987, Escobar lost two of his closest associates. In February Carlos Lehder was arrested, and in November, Jorge Luis Ochoa. Ochoa, however, was released after a riot in La Modelo prison.

Early the following year, a car carrying 154 pounds (70 kg) of dynamite exploded in front of the Monaco building, where the Escobar family lived. There were no fatalities, but the building was severely damaged, and although the Cali Cartel denied involvement, Escobar considered this event a formal declaration of war.

From then on, Escobar launched an offensive against the operations of his Cali rivals. In 1988, he set fire to and dynamited dozens of properties owned by the Rodríguez Orejuela family and began an espionage operation against them.

Terror years

The year 1989 was one of the bloodiest in the conflict between the cartels and the state.

At the end of 1988, the secretary general of the Colombian presidency, Germán Montoya, had attempted to approach the group of "los Extraditables", opening the possibility of dialogue. The Medellín Cartel then proposed to the state to grant them legal pardon and a demobilization plan to put an end to the conflict. The initiative was unsuccessful, largely due to the United States' refusal to negotiate with the criminals.

The Medellín Cartel was quick to respond, assassinating judges, government officials, and Colombian public figures. The bloodshed included the bombing of the Mundo Visión television station and the murder of presidential candidate Luis Carlos Galán, an enemy of drug trafficking and the person who had the best chance of being elected.

Galán's assassination spurred the Colombian state to declare war on narcoterrorism. Through new decrees, President Virgilio Barco Vargas approved special measures (some even contrary to the National Constitution) for the persecution and treatment of drug traffickers.

These measures included expedited extradition to the United States, the confiscation of drug traffickers' personal assets, and the creation of the Elite Group, composed of 500 specially trained agents to deal with "Los Extraditables". In the days that followed, the government carried out about 450 raids and arrested nearly 13,000 people linked to drug trafficking.

The Medellín Cartel responded with a declaration of total war. Between September and December of 1989, more than 100 explosive devices detonated in the cities of Bogotá, Medellín, Cali, Bucaramanga, Cartagena, Barranquilla, and Pereira. In addition to the acts of hired assassination, there were an estimated 300 terrorist attacks during those three months, resulting in a toll of nearly 300 civilian deaths and over 1,500 wounded.

However, the Colombian state did not give in. In November 1989, Escobar was close to being captured in an operation at the El Oro estate in Antioquia, where his brother-in-law Fabio Henao was killed and 55 of his men were captured. Later, on December 15, 1989, the second in command of the Medellín Cartel, the "Mexican" Rodríguez Hacha, was shot by the police on the country's north coast, along with his son and bodyguards.

As the noose tightened around them, "Los Extraditables" announced another call for dialogue with the government, first kidnapping the son of the secretary of the presidency, Álvaro Diego Montoya, and two relatives of President Barco. A brief truce ensued, and in the early 1990, a committee of Colombian notables was formed to negotiate with the narcoterrorists.

Escobar and his associates responded by releasing the hostages to show a genuine willingness for dialogue. In addition, they handed over a bus full of explosives and revealed the location of one of their clandestine laboratories in the town of Chocó. But the dialogue was in fact a ploy to buy time while initiating a large-scale operation in Envigado, Antioquia.

On March 30, the cartel ended the truce. Escobar put a price on the life of every police officer the criminals killed, unleashing an urban war that by the end of July had left hundreds dead and injured, including Senator Federico Estrada Vélez.

Government forces also committed excesses: in retaliation for the murder of nearly 215 police officers between April and July of 1990, their death squads carried out clandestine executions in the slums every night.

That same year in June, Escobar's military leader, John Jairo Arias Tascón, alias "Pinilla", was assassinated. Following an operation in Magdalena from which Escobar miraculously managed to escape again, the cartel announced a new truce in combat, just in time for the election of the new government of César Gaviria.

Imprisonment of Pablo Escobar

The new Colombian administration seemed willing to end the conflict as soon as possible. On August 11, the Elite Group killed Gustavo Gaviria Rivero, "El León," cousin and right-hand man of Pablo Escobar, in a shootout. The "patrón" began to lose his most reliable associates.

At the same time, Justice Minister Jaime Giraldo Ángel announced a legislative plan to facilitate the surrender of narcoterrorists, offering a reduction in their sentences and imprisonment in Colombia (the narcos feared extradition to the United States, above all) in exchange for voluntary surrender and confession of at least one crime committed.

The Ochoa brothers were the first of Escobar's high-level henchmen to accept the offer, between December 1990 and February 1991. The patrón, distrusting the government's word, began a series of selective kidnappings.

Several of these captives died in rescue attempts or were executed in retaliation for the government's actions. Escobar's idea was to pressure the government to design a plan tailored to his needs. But in the absence of a response, he resumed his methods of terrorism: between December 1990 and the early months of 1991, at least 44 people were killed in bombings and shootings, including former Justice Minister Enrique Low Murtra.

Eventually, the government had no choice but to give in to Escobar's demands. In June 1991, the boss of the Medellín Cartel surrendered to justice, to be confined in La Catedral prison in Envigado. From there, he continued to control his illegal operations remotely, thanks to his two associates in hiding: Fernando "El Negro" Galeano and Gerardo "Kiko" Moncada.

During his imprisonment, Escobar was attended to by his wife, "La Tata," and was in constant contact with his henchmen. He received many messages and documents in his room. At La Catedral he received visits from celebrities, beauty queens, and soccer players.

The room where Escobar was held at La Catedral was akin to a five-star hotel suite: a large bed, cozy decoration, TV sets, video and music players, imported furniture, a personal library, and carpeted floors. The prison also had pool rooms, a bar, and a soccer field. Parties, orgies, and business meetings were held nearby, as Escobar continued to lead his criminal operation from jail. The prison itself, as was later discovered, had been commissioned by Escobar himself on land that belonged to him.

In 1992, Escobar's actions became public knowledge, and the Gaviria government decided to transfer him to a "real prison". Aware of the decision, Escobar planned his escape with the assistance of his henchmen, and on July 22, he escaped by breaking through a plaster wall at the back of the prison.

Escobar's escape was a serious blow to the Gaviria government and the Colombian justice system. The creation of a "Search Bloc" composed of the police, the army, and the US DEA was immediately announced, and a reward of 2.7 billion pesos was offered for information leading to the "patrón's" capture.

Death of Pablo Escobar

Pablo Escobar's return to freedom was marked by a reality that was very different from the one he had left before his surrender. A fracture was growing in the Medellín Cartel and sectors opposed to his leadership eventually allied with his enemies in Cali. This broad alliance against him ended in October 1992 with one of his last military leaders, Brances Alexander Muñoz, alias "Tyson".

The resources of the Medellín Cartel began to dwindle, and their actions became more desperate. Car bombs exploded in Bogotá, Barrancabermeja, and other cities, killing civilians and officers indiscriminately. Escobar sought to renegotiate his surrender and authorized the delivery of some of his most trusted associates, but in response, actions against him intensified.

On January 30, 1993, a new actor joined the conflict: the paramilitary gang of "Los pepes" (acronym for "Perseguidos Por Pablo Escobar"), dedicated to pursuing and killing Escobar's front men, collaborators and cover-ups.

By March 1993, around 100 hit men and 10 of the cartel's military leaders had been killed, and nearly 1,900 collaborators arrested. Meanwhile, 300 other "gatilleros" (hired gun thugs) had been gunned down by rival gangs.

Escobar's wife and children had unsuccessfully sought asylum in the United States and Germany and lived under police surveillance, so they were used as bait by the authorities. On December 2, 1993, after 17 months of intense search, Escobar was cornered by the police in the middle-class neighborhood of Los Olivos, in Medellín.

There, the last of his hit men, Jesús Agudelo, alias "Limón", was killed, and Escobar tried to escape through the roofs of the neighboring houses, but he was shot three times and died on the spot. His death marked the end of the Medellín Cartel and was photographically recorded by the Search Bloc. He was 44 years old.

The next day, his death was announced as a major victory in the fight against drug trafficking. His family mourned his death along with thousands of supporters from the lower classes, who still paradoxically expressed their gratitude. His coffin was accompanied to the Montesacro Gardens cemetery in Itagüí by a massive procession.

This duality of his image made him both an infamous criminal and a popular hero. His life of violence and eccentricities has served as inspiration for numerous newspaper reports and fiction series.

Explore next:

References

- Palacios, R. (2022). “Celda cinco estrellas, reinas de belleza y orgías: la vida de Pablo Escobar en la cárcel que mandó a construir”. Infobae.

- Salazar, A. (2012). La parábola de Pablo. Penguin Random House.

- Rockefeller, J. D. (2015). Pablo Escobar: El auge y la caída del rey de la cocaína. Createspace.

- Tikkaken, A. (s. f.). Pablo Escobar (Colombian criminal). The Encyclopaedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/

- Villatoro, M. (2014). “La verdadera historia de Pablo Escobar, el narcotraficante que asesinó a 10.000 personas”. ABC cultural. https://www.abc.es/

Was this information useful to you?

Yes NoThank you for visiting us :)