We explore the life of Octavio Paz, and his main contributions to Mexican literature. In addition, we discuss his diplomatic career and its historical context.

Who was Octavio Paz?

Octavio Paz was a Mexican writer and diplomat regarded as one of the most prominent Latin American authors of the 20th century and a key figure in contemporary Spanish-language literature. His career as a poet and essayist earned him numerous national and international awards, including the Nobel Prize in Literature and the Cervantes Prize.

Alongside Chilean Pablo Neruda (1904-1973) and Peruvian César Vallejo (1892-1938), Octavio Paz was a central figure in postmodernist Latin American poetry. He was also a renowned intellectual, making significant contributions to thought and opinion, translation, and literary criticism, and an enthusiastic promoter of Mexican literature, involved in the creation of various poetic groups and literary magazines.

Throughout his life, Paz showed his cosmopolitan interests and social commitment, particularly during his stay in Spain, where he was involved in the Spanish Civil War engaging in anti-fascist activism. In his personal life, he was married twice: the first marriage was with the celebrated Mexican writer Elena Garro (1916-1998), with whom he had his only daughter, and the second with French artist Marie-José Tramini (1934-2018), with whom Paz lived until his death in 1998.

- See also: Horacio Quiroga

Childhood and formative years of Octavio Paz

Octavio Paz was born in Coyoacán, Mexico City, on March 31, 1914, into a family of intellectuals. It was the period of the Mexican Revolution, and his father, lawyer and journalist Octavio Paz Solórzano (1883-1935), supported Emiliano Zapata, leading the family to spend extended periods with Octavio's paternal grandfather, Irineo Paz (1836-1924), an intellectual and novelist. In their home in the Mixcoac neighborhood, the young Octavio Paz had access to a large library where he first became acquainted with literature.

In 1916, Octavio Paz's father was forced into exile, moving to Los Angeles, United States, with his family. Their years of exile ended with Emiliano Zapata’s death, in 1919. Back in Mexico, Paz began his studies at the National Preparatory School and later at the National University of Mexico (present-day UNAM), where he studied law, philosophy, and literature.

During his youth, Paz also formed himself politically. He identified with the political project of José Vasconcelos (1882-1959), a former rector of UNAM and Secretary of Public Education, whose presidential candidacy was supported by prominent intellectuals and university sectors. He also met the young Catalan anarchist José Bosch (1872-1936), and began to participate in various student and labor movements activism.

His literary interests were also precocious. At the age of sixteen, he published his first article, "Ethics of the Artist", in which he touched upon the morality of art and the dilemma between social commitment and "pure" art. That same year, he joined the founding group of the magazine Barandal (1931), alongside Rafael López Malo, Salvador Toscano, and Arnulfo Martínez Lavalle, and two years later in 1933, he published his first collection of poems: Luna Silvestre (Wild Moon).

In 1937, Paz left with his wife Elena Garro for Mérida, Yucatán, where he participated in the construction of a school for workers' children planned by the government of General Lázaro Cárdenas. While in Mérida, he received an invitation from Rafael Alberti (1902-1999) and Pablo Neruda to the Second International Congress of Writers for the Defense of Culture to be held in Spain during the Second Republic.

Marriage to Elena Garro

The marriage between Octavio Paz and Elena Garro lasted thirteen years, during which they had their only daughter, Laura Helena Paz Garro. Following their divorce in 1950, Garro's work was overshadowed by Paz's popular acclaim. Today, however, she is recognized for her enormous contributions to Mexican narrative and drama, being regarded as Mexico's second most important female writer, surpassed only by Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz.

The trip to Spain was of great importance in Octavio Paz's life. There, he met Pablo Neruda, César Vallejo, Vicente Huidobro (1893-1948), Nicolás Guillén (1902-1989), and other prominent intellectuals of the Generation of '98 and the magazine Hora de España. In addition, he visited the front lines of the Civil War and openly sympathized with the Republican cause, though his political ties with the international left were often troubled due to the repression of the Marxist Unification Workers Party in Catalonia and the crimes committed in the Soviet Union by Joseph Stalin (1878-1953).

Diplomatic career of Octavio Paz

Octavio Paz returned to Mexico in 1938, after the tragic death of his father, who was run over by a train. In Mexico, he played a key role in the literary magazines Taller (1938), Tierra Nuestra (1940), and El Hijo Pródigo (1943), all of them important in the history of Mexican literature. It was during this period that he produced his greatest literary work. In 1943, he won a Guggenheim Fellowship to resume his studies in Berkeley, United States.

Following World War II, Paz was offered a position in the Mexican diplomatic service. Until 1951, he was part of the Mexican consular delegation in France, and while in Paris, he came into contact with the emerging Surrealist movement. He collaborated with the famous magazine Esprit, founded by Emmanuel Mounier in 1932, and established relationships with Jean-Paul Sartre (1905-1980), Albert Camus (1913-1960), and André Breton (1896-1966).

His work in Mexican diplomacy took him to India in 1952, and later to Japan as chargé d'affaires, which allowed the two nations to resume diplomatic ties suspended during World War II. While in these countries, Paz became acquainted with Asian religions and Eastern mysticism, important themes in his literary works.

Back in Mexico, Paz was charged with the Office of International Organizations of the Mexican Foreign Ministry between 1953 and 1959. He played a prominent role in the magazine Revista Mexicana de Literatura, which promoted the idea of a middle stance, between the left and the right, and participated in the poetry-theater group “Poesía en voz alta”, and in the magazine El corno emplumado.

He was sent back to Europe in 1959, and while in Paris, he met his second wife, Marie-José Tramini. Three years later, he was appointed Mexican Ambassador to India, a position he held until 1968. That year, following the Tlatelolco Massacre, Paz resigned from his post in protest, the only Mexican ambassador to do so formally. From then on, he worked as a university professor in the United States.

Last years of Octavio Paz

During the 1970s and 1980s, Octavio Paz continued to be an influential figure within Mexican intellectual circles. He was the founder and editor of the magazines Plural (1971) and Vuelta (1976), embracing literary experimentation and addressing human rights violations by both right-wing and communist regimes of the time.

In a 1984 interview for the Spanish newspaper El País, Paz stated: "When I compared Castro to Pinochet, I did so because both are dictators. If one criticizes a dictatorship, one must also criticize all dictatorships". This stance alienated him from most Mexican and Latin American intellectuals.

Nevertheless, his work continued to receive recognition. In 1981, he was awarded the Cervantes Prize, the highest literary distinction in the Spanish language, and in 1990, he received the Nobel Prize in Literature.

In 1996, his apartment was destroyed in a fire, and with it much of his library. He was relocated by the Mexican government to the historic Casa de Alvarado in Coyoacán, where he lived until his death at the age of 84 on April 19, 1998.

Poetry of Octavio Paz

The poetic works of Octavio Paz are difficult to classify, being as broad and deep as his interests. They encompassed the major poetry trends of the 20th century, such as Romanticism, Modernism, Symbolism, and Avant-garde, while also touching upon varied themes such as eroticism, social change, esotericism, Eastern mysticism, and particularly the loneliness and isolation of the individual.

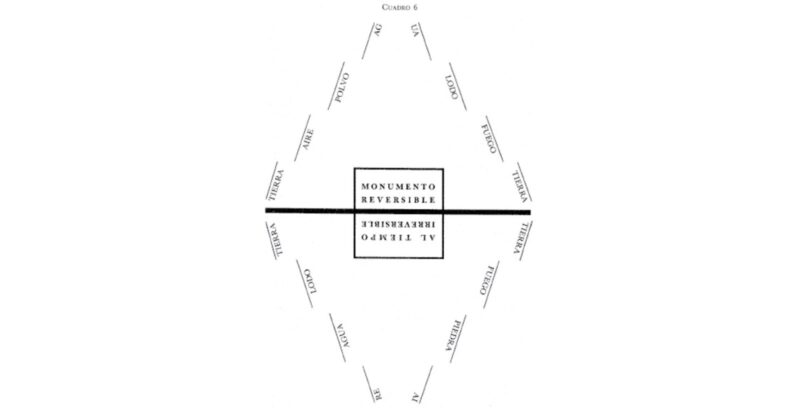

At the same time, his poetry fluctuates between the pursuit of formal perfection, through metrics and traditional formats, and the typical experimentation of Surrealism and Avant-garde movements. In fact, Paz is the creator of topoemas (deriving from Greek topos, "place", and poem), an intellectual form of poetry employing visual signs other than those of traditional writing.

Such complexity has led various critics to classify Paz's poetry as existentialist, neo-modernist, surrealist, and metaphysical all at once. It is cosmopolitan poetry that, according to Chilean writer and diplomat Jorge Edwards (1931-2023), "accompanies thought, provokes it, extends it, and at the same time summarizes it."

Among the most notable poetic works of Octavio Paz are:

- ¡No pasarán! (1936)

- Entre la piedra y la flor (1941)

- Piedra de sol (1956)

- Libertad bajo palabra. Obra poética (1935-1957) (1960)

- Salamandra (1962)

- Blanco (1967)

- Topoemas (1971)

Essays of Octavio Paz

The essays of Octavio Paz are as well known and celebrated as his poetic work, if not more so. In his essays Paz addresses various topics of sociological, anthropological, political, historical, and literary interest, leading his biographers to dub him "a man of his century", an individual in tune with the concerns of his time, whose interests transcended the strictly national.

Many believe that his essays reaffirmed, in a context of profound changes in Western culture as was the 20th century, the validity and value of the essay as a literary genre, that is, as an art form and not just as a scientific and objective medium.

Among the most notable essays of Octavio Paz are:

- El laberinto de la soledad (1950)

- El arco y la lira (1956)

- Los hijos del limo. Del romanticismo a la vanguardia (1974)

- Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz o las trampas de la fe (1982)

- La llama doble (1993)

References

- Edwards, J. (s. f.). En la mirada de Jorge Edwards. Zona Paz. https://zonaoctaviopaz.com/

- Forgues, R. (1992). Octavio Paz: el espejo roto. EDITUM.

- Ministerio de Cultura de Argentina. (2021). “Octavio Paz: ‘Mi destino, pensé desde niño, era el destino de las palabras”. https://www.cultura.gob.ar/

- Mueller, E. (1984). “Octavio Paz: nunca he elogiado ninguna dictadura”. El País, Cultura, 19 de agosto de 1984. https://elpais.com/diario/

- Sánchez Zamorano, J. A. (1999). “Historia y poesía en Octavio Paz”. Anales de literatura hispanoamericana, n. 28. pp. 1205-1221.

- The Encyclopaedia Britannica. (2023). “Octavio Paz (mexican writer and diplomat)”. https://www.britannica.com/

Explore next:

Was this information useful to you?

Yes NoThank you for visiting us :)