We explore the life and work of Nicolaus Copernicus, and discuss the basis of his studies.

Who was Nicolaus Copernicus?

Nicolaus Copernicus (1473-1543) was a Polish-Prussian Renaissance mathematician, astronomer, jurist, physicist, Catholic cleric, and military leader noted for formulating the heliocentric theory of the solar system, according to which the Sun rather than Earth occupies the central axis around which the rest of the heavenly bodies revolve.

Copernicus dedicated his life to study; thus he attended the Universities of Krakow and Bologna, where he studied mathematics, law, medicine, Greek, philosophy, and later, during a brief stay in Rome, science and astronomy. It was in the latter field that he was to make his most significant contributions.

Despite this, and in view of the groundbreaking impact that his studies were to have on the prevailing worldview of the time, which contradicted the Aristotelian precepts upheld by the Church (particularly, the geocentric model), Copernicus did not publish his work, which saw the light of day posthumously.

- See also: René Descartes

Heliocentric theory

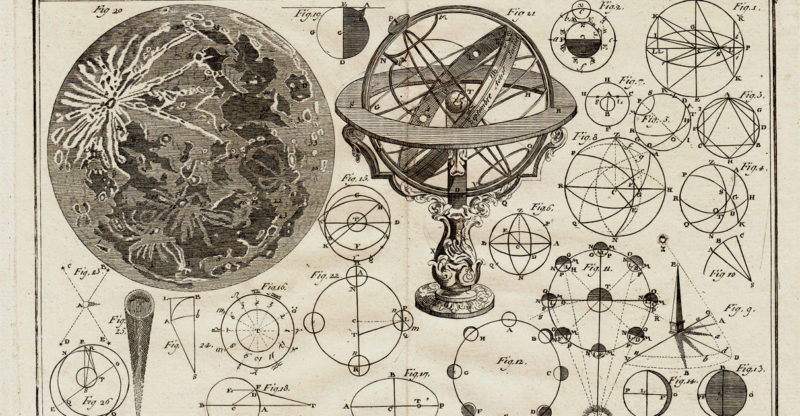

The fundamental principles of the theory Copernicus developed over 25 years of study took up the work of Greek astronomer and mathematician Aristarchus of Samos, proposing the following postulates:

- The movements of celestial bodies are circular, eternal, uniform, or compounded of several cycles.

- The center of the Universe is located near the Sun.

- Planets revolve around the Sun (the outer planets had not yet been discovered).

- The stars are distant and fixed objects that do not revolve around the Sun.

- Planet Earth has three motions: daily rotation, annual revolution, and annual tilting of its axis.

- The movements of the Earth account for the retrograde motion of planets.

- The distance between the Sun and the Earth is little compared to the distance from the Earth to the stars.

Censorship

The exact reasons for Copernicus not publishing his work during his lifetime are unknown. Many suspicions point to the fact that in 1536, already close to his definitive theory, and with rumors about his studies having spread throughout Europe, he was summoned by the Archbishop of Capua, Nicolas von Schönberg, to appear and explain his theories. This summons seems to indicate the ecclesiastical pressure to which Copernicus would yield.

Other scholars point out that Copernicus feared criticism, reinforcing his faith in the scientific rather than in the religious model.

Publication

The book containing his astronomical work was entitled De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (On the Revolutions of the Celestial Spheres), published by German theologian and literary editor Andreas Osiander in 1543.

In it Copernicus studies numerous Greek philosophers, especially the Pythagoreans, but surprisingly makes no reference to Aristarchus of Samos, the earliest scholar in history to consider the heliocentric model.

Break

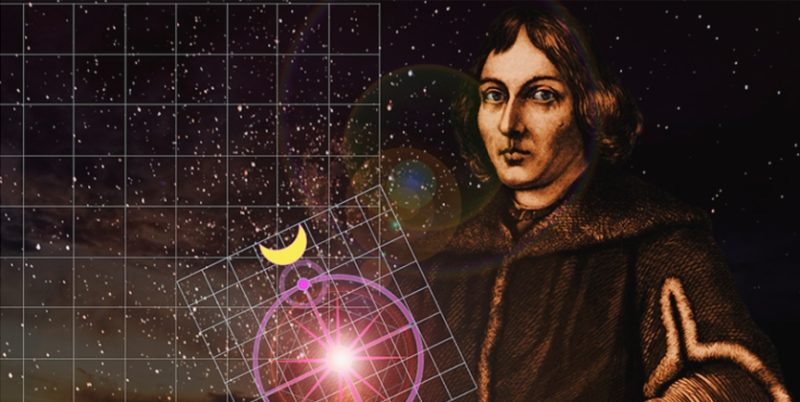

The major break that Copernicus' work represented was of a cosmological, and particularly religious nature, since the ideas held throughout the Middle Ages by the dogma of the Catholic Church, which was based on the texts of Greek philosopher Aristotle, presupposed a closed and hierarchical Universe with the Earth at its center given its importance in the divine creation.

The Copernican model, on the other hand, proposed a vast and indefinite universe, practically infinite, with its center near the Sun.

Structure

De revolutionibus orbium coelestium is composed of six books, each with a specific proposition:

- First Book: A general overview of the heliocentric model.

- Second Book: The principles of spherical astronomy and a catalog of the fixed stars.

- Third Book: The apparent motions of the Sun and related phenomena.

- Fourth Book: The Moon’s motions.

- Fifth Book: The concrete explanation of the new system based on previously outlined information.

- Sixth Book: A continuation of the concrete explanation from the previous book.

Legacy

His theories and explanations are considered the cornerstone of numerous subsequent works that were equally groundbreaking, such as those by Galileo Galilei and Isaac Newton; hence their contribution is often referred to as the "Copernican Revolution".

A sign of the times

The significance of the Copernican model is such, in its break from the prevailing religious model, that it is considered a sign of the profound and radical changes that were to take place with the Scientific Revolution and the development of humanism as the prevailing ideology. In other words, it marked the birth of faith in human reason and the scientific capacity to understand the world.

Rejection

Rejection of Copernicus’ works, however, came with the Holy Inquisition of the Catholic Church, which opposed and persecuted the defenders of heliocentrism. In fact, his books were included in the Index Librorum Prohibitorum, the Index of Prohibited Books by the Church.

Death

Copernicus died of a stroke at the age of 70. His remains were found in 2005 by an archaeological team in the Cathedral of Frombork, Poland, and were genetically verified against a strand of hair found among his writings. This discovery made it possible to advance a theory on how his face would have been like.

Recognition

When the consequence of Copernicus’ discoveries had been fully recognized and understood, his name was included in the Lutheran liturgical calendar. In addition, a lunar crater and an asteroid, (1322) Copernicus, bear his name. In 2010, he was reburied under a black tombstone with the Copernican model on its surface.

Explore next:

Was this information useful to you?

Yes NoThank you for visiting us :)