We explore the life and works of Horacio Quiroga, and discuss his experiences in the jungle in northern Argentina.

Who was Horacio Quiroga?

Horacio Quiroga was a Uruguayan author, playwright, and poet considered one of the most prominent Latin American short story writers, the founder of a tradition that continues to this day, and heir to the American short story writer Edgar Allan Poe (1809-1849).

During most of his life, Quiroga worked as a journalist, teacher, and justice of the peace, but it was his short stories that brought him wide recognition and acclaim. His tales of the jungle, for which he found inspiration in the jungle of Misiones in northern Argentina, are celebrated, as are his sinister and bloody tales of the macabre like "The Decapitated Chicken" and "The Feather Pillow".

Quiroga reflected on the short story as a literary genre, producing his famous "Ten Commandments for the Perfect Storyteller", in which he proposes the ten fundamental considerations that any short story writer should follow.

Quiroga's life was marked by depression and death, and ended tragically at the age of 58 when he committed suicide by ingesting cyanide. He had been diagnosed with an untreatable and inoperable cancer.

- Also see: Virginia Woolf

Birth and childhood of Horacio Quiroga

Horacio Quiroga was born on December 31, 1878 in the Uruguayan city of Salto, by the Uruguay River, into a bourgeois family: his father was the Argentine consul in Uruguay, related to the caudillo Juan Facundo Quiroga (1788-1835).

Death was present in the home from an early age. When Horacio was just a few months old, his father died in a hunting accident. In 1891, his mother, Pastora Forteza, remarried, and in 1896 her new husband, Mario Barcos, suffered a stroke that left him paralyzed. That same year, Quiroga's stepfather decided to take his own life by shooting himself in the head with a shotgun. Horacio, who was only 18, witnessed this terrible event upon entering the room.

By then, Quiroga had completed high school and his technical studies in the city of Montevideo, showing an interest in literature, chemistry, photography, and especially cycling and country life. He would spend long hours in machinery and tool repair workshops, and made bicycle trips to nearby towns.

A devotee of philosophical materialism, he began writing his first texts (poems) between 1894 and 1897. Around that time, he began to collaborate in Uruguayan magazines like La revista and La reforma, and in 1898 he fell in love for the first time with María Esther Jurkovski, whose parents did not approve of the union. This unrequited love would inspire Quiroga to write several works later on.

Horacio Quiroga's trip to Paris

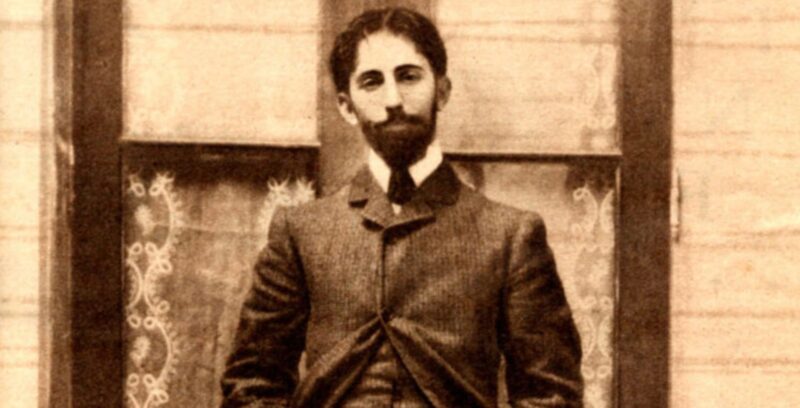

Quiroga used the inheritance from his stepfather to travel to Paris, a milestone in the life of young intellectuals at the time. There, a transformation took place: the educated young man who left Montevideo in first class returned in third, ragged and disheartened, after having wandered impoverished for four months in the French capital. From then onward, he would wear the bushy black beard that would become characteristic of him.

Back in Uruguay, Quiroga published his Parisian experiences in his Diario de un viaje a París (Journal of a Trip to Paris), before moving to Montevideo. There, he founded a literary group with other fellow writers and friends including José María Delgado (1884-1956), Federico Ferrando (1877-1902), and particularly Alberto J. Brignole and Julio J. Jauretche, whom he had known since adolescence. This group came to be called the "Consistorio del Gay Saber" (The Consistory of The Gay Science), influencing the local literary life during its two years of existence.

In 1901, his first book, Los arrecifes de coral (Coral Reefs), appeared, which was a compilation of more than fifty texts in verse and prose dedicated to Argentine poet Leopoldo Lugones (1874-1938), whom he greatly admired That same year, death knocked at his door again: two of his siblings, Prudencio and Pastora, died of typhoid fever.

Shortly afterwards, while Horacio was cleaning and checking the revolver with which his friend and colleague Federico Ferrando planned to fight a duel, the gun was accidentally triggered, taking Ferrando's life. Quiroga was arrested and interrogated by the police, and spent four days in jail while the accidental nature of the homicide was proven.

Upon regaining his freedom, Quiroga dissolved the Consistory of The Gay Science and in 1902 decided to leave Uruguay forever. He settled down in Argentina, finding work as a teacher, and stayed with his sister María in Buenos Aires. He collaborated with several magazines and newspapers, among them Caras y caretas, PBT, and La Nación.

Horacio Quiroga and the jungle of Misiones

Quiroga's first journey to the jungle of Misiones was in 1903, when he accompanied Leopoldo Lugones on a research trip to the Jesuit ruins in the region. Quiroga went as a photographer, and the jungle captured his heart from the first image he took. So much so that in 1906 he purchased land in Misiones and planned his life far from the city.

Prior to that, Quiroga had made his debut as a storyteller to resounding success. In 1904, his first book of short stories was published: El crimen del otro (The Crime of Another), praised by José Enrique Rodó (1871-1917) and strongly influenced by the work of Edgar Allan Poe. From then on, he would often be compared to the great American master of the short story.

In 1905, his short novel Los perseguidos came out, recounting his early experiences in the jungle. But it was his collaborations in magazines like Caras y caretas that earned him great fame, particularly following the publication of his famous short story "El almohadón de plumas" ("The Feather Pillow"). At the height of his popularity, Quiroga published around eight stories a year in these magazines.

Eager to leave the city, Quiroga acquired 185 hectares of land in San Ignacio, in the jungle of Misiones, and began planning the place where he would later live. At that time, he was a professor of Spanish and literature, and devoted his 1908 vacation entirely to the construction of a bungalow on the banks of the Alto Paraná.

Quiroga's first marriage

Quiroga fell in love with one of his high school students from Colegio Normal 8, Ana María Cires, to whom he dedicated his 1908 literary work Historia de un amor turbio (History of a Troubled Love). Despite the opposition of her parents (who were of French origin), Quiroga proposed to her in 1909.

That same year they married and left Buenos Aires to settle down on the land in Misiones. Meanwhile, Quiroga resigned from his teaching position to devote himself to his yerba mate fields and was later appointed as a justice of the peace in San Ignacio, a position he performed rather poorly.

In 1911, their first daughter, Eglé, was born in the solitude of their jungle hut, and the following year their son, Darío, was born in Buenos Aires. Quiroga dedicated enormous attention to his children: he personally took care of their education, teaching them how to cope with the jungle, raise animals and shoot a shotgun.

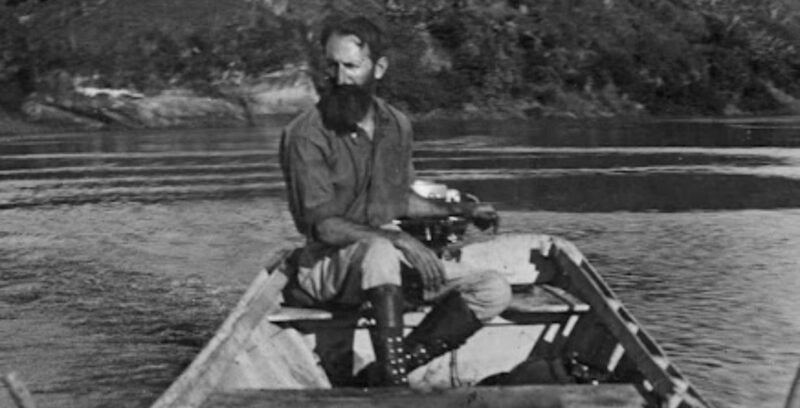

While living in the jungle, Quiroga made everything with his own hands, being a barber, tailor, pedicurist, and even hunting wild animals. The rest of his time was spent writing, a never-ending task. However, the couple's life was fraught with economic hardships: neither the cultivation of oranges, nor his salary as a civil servant or the money from collaborations in Buenos Aires magazines were significant sources of income.

Finally, in 1915, his wife ingested a strong dose of a chemical compound for developing photographs, dying after a week of agony. Deeply affected, Quiroga buried her in San Ignacio and never visited her grave again. At the end of 1916, he decided to return to Buenos Aires with his children.

Quiroga's return to Misiones

From 1916 to 1925, Quiroga lived in Buenos Aires, holding diplomatic positions in the Uruguayan consulate. His life revolved around his children and his writing, which was then undergoing a great period. His tormented experiences gave rise to prominent works such as Cuentos de amor de locura y de muerte (Tales of Love, Madness and Death) from 1917, Cuentos de la selva (Jungle Tales) from 1918, and El salvaje (The Wild) from 1919.

In 1920, he founded the literary society "Agrupación anaconda" (Anaconda Association), and collaborated with various magazines and the newspaper La Nación. He wrote his first and only play, Las sacrificadas (The Slaughtered), premiered in 1921, as well as his only screenplay, La jangada florida (The Florida Raft), which was never filmed. During this period, he had a romance with Argentine poet Alfonsina Storni (1892-1938), whom he often mentioned in his correspondence.

Quiroga decided to return to Misiones, falling in love again, this time with a 17-year-old girl named Ana María Palacio. However, their love did not prosper as her parents took her to live abroad. The heartbreak inspired Quiroga to write El pasado amor (Past Love), a novel published in 1929, and to build a boat with his own hands that he named “gaviota”, in which he sailed downriver from San Ignacio to Buenos Aires.

In a letter to Ezequiel Martínez Estrada (among Argentina's greatest essayists and one of his best friends, whom he called "brother"), Quiroga thus explained his relationship with the jungle:

I will only see tomorrow or the day after in the deep sleep that nature offers us, its most peaceful rest. I will die, watering my plants, and planting on the very day I die. I am doing nothing but integrating myself into nature, with its laws and darkest harmonies, even to us, but existent.

From: Las raíces de Horacio Quiroga (The Roots of Horacio Quiroga, 1961) by Emir Rodríguez Monegal.

In 1926, back in Buenos Aires, Quiroga rented a country house in Vicente López, on the outskirts of the city. This time constituted his third and most mature literary period, epitomized by his 1927 book of short stories Los desterrados (The Exiles). He received numerous tributes to his work and figure, despite the fact that his novel El pasado amor (Past Love) sold only forty copies.

Quiroga married for the second time in 1927, to María Elena Bravo, a schoolmate of his daughter Eglé, who was about 20 years old. The following year, his third daughter, María Helena, nicknamed "Pitoca", was born.

Illness and death of Quiroga

By 1932, Quiroga's married life was no longer happy. The writer increasingly refused to comply with the schedules and demands of his work with the Uruguayan consulate, and was plagued by jealousy due to his wife's youth. Added to this was a feeling of rejection by the new generation of writers.

Eventually, Quiroga decided to move back to Misiones. He managed a transfer of his bureaucratic duties and settled in San Ignacio with his family after declining an offer to join the Uruguayan consulate in Russia. However, life in the jungle did not bring the hoped-for happiness: his wife could not adapt, and in addition, a change in government in Uruguay meant the end of his diplomatic service.

Nevertheless, thanks to the help of friends his economic situation improved: he managed to apply for Argentine retirement, and soon after was appointed honorary consul of Uruguay, receiving a life annuity of 50 pesos. That same year, Quiroga published his last collection of short stories, Más allá (Beyond). It was around this time that he began to experience the first symptoms of a prostate disease.

When his ailments became unbearable, María Elena persuaded Quiroga to move to the city of Posadas so that he could receive medical care, where he was diagnosed with prostatic inflammation. Shortly afterwards, his wife and daughter left him definitively, returning to Buenos Aires.

In 1937, he was admitted to the Hospital de Clínicas in Buenos Aires, where he was treated and diagnosed with inoperable cancer. Facing a painful and inevitable death, Quiroga decided to take his own life. On the night of February 19 of that year, he swallowed a glass of cyanide, dying a few minutes later.

Horacio Quiroga's body was laid in state at the Casa del Teatro de la Sociedad Argentina de Escritores (SADE), of which he had been the founder and vice-president. His remains were repatriated to Uruguay, despite his wishes to be cremated and his ashes scattered in the jungle of Misiones.

A few years before her own suicide, Alfonsina Storni bid farewell to her friend Horacio Quiroga with the following verses:

To die like you, Horacio, in your right mind,

and just as always in your stories, is not bad;

a timely lightning bolt and the fair is over...

They will say.One does not live in the jungle with impunity,

nor facing the Paraná.

Well done with your steady hand, great Horacio...

They will say.From: Poems (2017).

Literary work of Horacio Quiroga

Throughout his life, Horacio Quiroga produced a remarkable body of work, particularly notable for his short stories. His style lies between the ornate language of Rubén Darío's Modernismo (1867-1916) and the morbid dramatic prose of Edgar Allan Poe. He was greatly indebted to the naturalism of Guy de Maupassant (1850-1893), and especially to British author Rudyard Kipling (1865-1936), whose "The Jungle Book" (1894) echoes in Quiroga's works.

His oeuvre, of a realistic type, often flirts with the fantastic, and is typically set in the jungle of Misiones or its surroundings, where topographical elements, fauna, and climate are prominent. His tales, imbued with pain, horror, and despair, deal with subjects considered taboo at the time, establishing Quiroga as a daring author ahead of his time.

Today, Horacio Quiroga's short stories, along with his "Ten Commandments for the Perfect Storyteller", is recommended reading for new generations of storytellers, especially tales like "El hijo" ("Son"), "La gallina degollada" ("The Decapitated Chicken"), "El almohadón de plumas" ("The Feather Pillow"), or "El hombre muerto" ("The Dead Man"). Finally, Quiroga is regarded as the first film critic in the history of Uruguay.

Among Horacio Quiroga's most renowned works are:

- Cuentos de amor de locura y de muerte (Tales of Love, Madness and Death - 1917)

- Cuentos de la selva (Jungle Tales - 1918)

- Anaconda y otros cuentos (Anaconda and other stories - 1921)

- Los desterrados (The Exiles - 1926)

References

- Crow, J. A. (1939). “La locura de Horacio Quiroga”. Revista Iberoamericana, vol. 1, n.1, pp. 33-45.

- Delgado, J. M. y Brignole, A. (1939). Vida y obra de Horacio Quiroga. C. García y cía.

- Jitrik, N. (1959). Horacio Quiroga. Una obra de experiencia y riesgo. Ediciones Culturales Argentinas.

- Orgambide, P. (1997). Horacio Quiroga: una biografía. Planeta.

- Paganini, A., Paternain, A. y Saad, G. (1969). Cien autores del Uruguay. Centro Editor de América Latina (CELA).

- Rodríguez Monegal, E. (1961). Las raíces de Horacio Quiroga. Asir.

- Storni, A. (2017). Poemas. Biblioteca del Congreso de la Nación (Argentina).

Explore next:

Was this information useful to you?

Yes NoThank you for visiting us :)