We explain who Socrates was and how he revolutionized the concept of philosophy. In addition, we explore his main characteristics and principal teachings.

Who was Socrates?

Socrates is one of the most prominent Western philosophers of all time. He was born in Athens, Greece, in 470 BC, and died in 399 BC. As he did not produce any written work, all the information about his thought, life, and work comes down to us from the accounts of his most famous disciple, Plato, who made him the principal interlocutor in most of his works. Aristophanes included him in his plays too, as did Xenophon in his dialogues. Other disciples of Socrates were Antisthenes, Aristippus and Aeschines.

Socrates was a remarkable teacher. By the age of 40, he taught in the streets, at banquets and in the agora, as the squares of the Greek polis were called. His teachings were free and oral; he encouraged his audience to reflect on what they considered to be true and usually called them to self-examination.

Socrates marked a turning point in the history of philosophy. With him emerged a kind of thought based on dialogue, critical thinking and the scrutiny of general commonly held truths.

He is best known for having initiated the idea of Socratic universals. These consisted of the definition of a concept, a moral virtue in most cases, which frames behavior in everyday life.

- See also: Aristotle

The life of Socrates

Socrates was born in Athens, in 470 or 469 BC. As we know from Plato, he was executed in 399 BC. His parents were Sophroniscus and Phaenarete of the deme of Alopece (deme from the Greek δῆμος, meaning "population" in the administrative sense).

It is believed that his mother was a midwife and his father a stonemason or sculptor. From the Platonic dialogues, we know that Socrates participated in at least three battles of the Peloponnesian War, fighting alongside Laches and saving the life of Alcibiades, as Alcibiades himself mentions in The Symposium.

Various sources depict Socrates as a married man, father of three children and friend of many young people and thinkers of the time. Plato recounts Socrates' views and opinions regarding different philosophical ideas and moral values. His passion concerning the usefulness of the ideals of beauty and goodness is often contrasted with his own rather ungraceful physical appearance, which was often the subject of mockery, even by later philosophers such as Nietzsche.

Socrates aimed at pursuing definitions for all virtue, and advised people to care for their soul and their capacity for reason and knowledge before caring about their physical appearance, which may be somewhat contradictory.

The idea that goodness and beauty were defined by their degree of usefulness reveals the Athenian philosopher’s thought. In the dialogues of Plato or in the works of Xenophon, he is portrayed as someone who could confound others and then direct their thinking towards new previously unconsidered positions. He did so only by questioning; most of the questions regarding common sense. His intent was to value things for their own end and to show how something functional was more beautiful than something purely aesthetic.

During his mature years he mostly kept aloof from politics. In addition to having served in the army during the war, he had taken part in several debates and had been politically active in the city of Athens. Though he never held any official political office (something he boasted about), his political involvement is what cost him his life. Socrates disagreed with the democratic system but he never acted against the laws of the city.

At the end of the Peloponnesian War, in 404 BC, a group of men seized power in the city of Athens and established an oligarchic regime known as the Thirty Tyrants. Many of them were friends or companions of Socrates though he did not approve of the violence of their actions. After seizing power, the Thirty Tyrants ordered Socrates to arrest Leon of Salamis, a wealthy man in a good position.

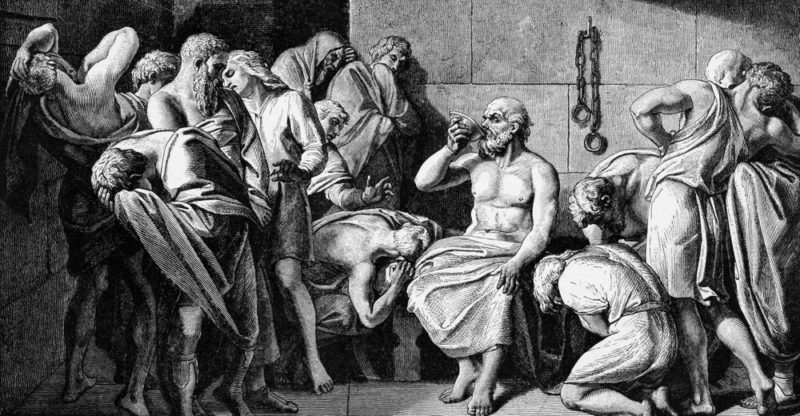

Socrates, objecting to the use of violence as a political resource, refused and disobeyed their orders. For this act of rebellion he was only saved by the counterrevolution that restored democracy. However, the new democrats knew the members of the Thirty Tyrants (such as Critias, Alcibiades and their companions) were close to Socrates. As they were not men of violence, they chose to accuse him in writing and bring him to trial. The main accuser was Meletus, who signed the letter alongside Anytus, a powerful man at the time. The text accused him of impiety and corrupting the youth.

Rather than fleeing the city or proposing a punishment other than death, Socrates defended himself, thus asserting his life's work. He was sentenced to death, and contrary to the advice of his friends, decided to abide by the law and was executed by being forced to drink hemlock. Both his defense and his last conversations are recounted in the Apology and the Phaedo, both dialogic works of Plato.

The legacy of Socrates

One of the most fundamental contributions of Socrates is the view that philosophy should serve a practical purpose for improving men’s lives. Philosophy should teach the art of living. This involves a deep understanding of various philosophical elements, such as good and evil, virtue or piety and their everyday usefulness. Only in this way can an individual approach knowledge.

Socrates did not write down any of his teachings. He believed that if he did, his ideas could be misunderstood. All that is known about him comes from the accounts of his disciples, particularly, from Plato. In most of his dialogues, Socrates is the main character with the exception of two of them, written during Plato's old age where Socrates plays a secondary role. The same is true of many of the works of Xenophon and those of Aristophanes.

Nonetheless, authoring no text makes the historical Socrates a much more interesting, puzzling and elusive character in the history of philosophy. His philosophical approach, as portrayed by his disciples, laid the groundwork not only for the everyday practice of philosophy, the role of the teacher or the approach to questions but also for the purpose that philosophy as a whole must fulfill.

The Socratic Method

The Maieutic Method

Socrates' thought is best known through Plato’s dialogues. They consist of a series of questions and answers between the philosopher and his pupils. This question and answer dialogue is known as the Socratic or maieutic method, which it is used to the present day.

When referred to as "maieutic", it is described as a process similar to childbirth. Maieutics is a way of helping the interlocutor find the truth that is inscribed within his soul. Thus, this method seeks to attain truth through dialogue, questioning again and again what has been said.

It is Socrates himself who compares his procedure to giving birth. In The Symposium, he recounts how the priestess Diotima asserts that every man's soul desires to give birth and therefore, the philosopher's task is that of a midwife, who assists in the birth of knowledge or logos.

Maieutics is even translated as "midwife" or "obstetrics", Socrates' mother profession. Even in the Theaetetus, Socrates reminds his interlocutor that his mother was a midwife and that he fulfills the same role concerning the souls of men, helping to give birth to the knowledge within their souls.

Dialogical structure of the method

Structurally most of the Platonic dialogues in which Socrates appears maintain the same argumentative form. It consists of a typical series of steps based on questions and answers, divided into two main parts: Socratic irony and maieutics as procedure in the strict sense.

The former can be summarized in two discursive attitudes that Socrates adopts: Socratic irony and refutation. In fact, the method as a whole is often called "Socratic irony". Regardless of the name, the attitudes Socrates embodies are the following:

- Irony. It is the way of feigning ignorance regarding some knowledge or subject matter. Faced with an interlocutor who assumes himself as an expert on the matter to be examined, Socrates feigns ignorance about the subject matter, acting as the curious questioner and questioning it ironically. This attitude is allegedly a form of self-mockery, since he was considered "the wisest man in Athens".

- Refutation. It is the proof that the expert's beliefs and arguments are contradictory. Through refutation, the person's own ignorance becomes evident.

What follows in many of Plato's works is that, in the best case, Socrates' interlocutors reach aporia: they have discarded their old opinions but find themselves in a dead end. If at the beginning of the dialogue the interlocutor believes he knows what piety means, for example, at the end he knows it was not what he thought and yet he still does not know what it is.

Following irony and refutation is maieutics. Once the interlocutor is stripped of his old beliefs, the dialogue continues, with the help of Socrates (as if he were a midwife), in such a way that the knowledge already inscribed in the soul of the one being assisted is born or brought forth, as recounted in The Symposium and Theaetetus.

"I know that I know nothing"

Socrates doubts everything; he even doubts those considered wise in his time. According to the story, his friend the wise Chaerephon, went to the Oracle of Delphi and asked if there was anyone wiser than Socrates, to which the Pythia responded "there was no one wiser in all of Athens”. Nevertheless, Socrates disavowed the oracle.

The difference between the sages of the time and Socrates is that while the sages believed themselves to be absolute sages with absolute wisdom, Socrates acknowledged his wisdom but also his ignorance. Hence, his famous phrase "I know that I know nothing". It is worth clarifying that this saying is an approximation of what he might have once said. If we stick to the Platonic dialogues, it is a paraphrase of some of his dictums.

For example, in Plato's Apology of Socrates, in the midst of a discussion, he says: "This man, on the other hand, thinks he knows something, when he does not know [anything]. On the other hand, I, who also do not know [anything], do not believe [I know something]". Strictly speaking, Socrates does not claim not to know, but rather he recognizes himself as ignorant. It is at this point where his true wisdom lies.

The concept of good and evil

For Socrates, vice is the expression of ignorance. In contrast, all virtue is a sign of knowledge. Knowledge is fundamental, since it is through it that one gains access to truth and for Socrates, everyone who possesses fair and right knowledge will do what is right or best. On the other hand, those who do wrong, do so out of ignorance and not out of malice. The human being is good by nature but does wrong only out of ignorance of the truth. This is the essence of true ignorance, as Socrates conceives it and presents it.

Speech and writing

Socrates delivered all his speeches or classes in public places and did so orally: for him discussion was more powerful in speech.

In any case, it is important to consider that at that time nearly all the Athenian population was illiterate; therefore oratory was for him a fundamental communication tool to attain the knowledge of truth.

Knowledge and wisdom

For Socrates, knowledge is not limited to the accumulation of learning but rather, it is in part that which is inscribed within humans on which new knowledge is built. Furthermore, knowledge for Socrates must fulfill and address practical needs; otherwise, it is inert knowledge.

References

- Guthrie, W. (1988). Historia de la filosofía griega, vol. IV. Platón, el hombre y sus diálogos: primera época. Gredos.

- Guthrie, W. (1988). Historia de la filosofía griega, vol. V. Platón, segunda época y la Academia. Gredos.

- Guthrie, W. (1994). Historia de la filosofía griega, Vol III. Siglo V. Ilustración. Gredos.

- Guthrie, W. (1953). Los filósofos griegos. De Tales a Aristóteles. FCE.

Related articles:

Was this information useful to you?

Yes NoThank you for visiting us :)