We explore the life and works of Federico García Lorca, and his contributions to Spanish and Latin American literature. In addition, we discuss his tragic death.

Who was Federico García Lorca?

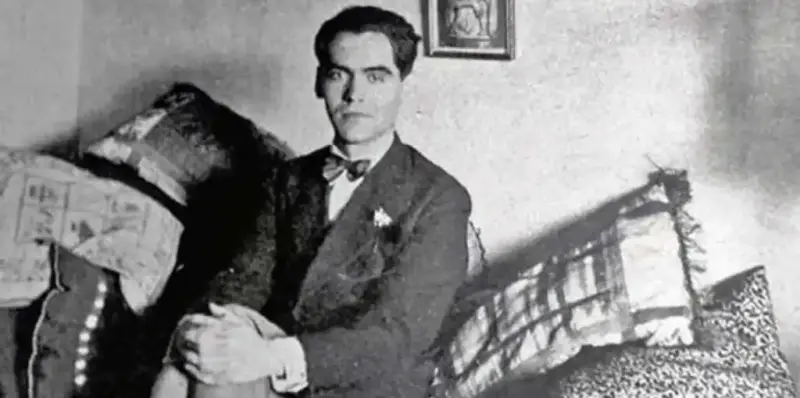

Federico García Lorca was a Spanish poet, playwright, and musician regarded as one of the most prominent and influential figures in 20th-century Spanish culture. In his brief literary career, spanning just 19 years, he composed some of the most celebrated poems and plays in contemporary Spanish literature, playing a fundamental role in revitalizing the Spanish-language literary tradition.

Lorca was a distinguished member of the so-called "Generation of '27", an avant-garde literary movement that comprised authors such as Pedro Salinas (1891-1951), Luis Cernuda (1902-1963), Dámaso Alonso (1898-1990), and Rafael Alberti (1902-1999). This heterogeneous group of writers championed an intellectual approach to literature, moving away from sentimentality, and artistically succeeding the celebrated "Generation of '98".

García Lorca's life is closely associated with the struggle between the liberal and conservative segments of society, a tragic opposition that led Spain into a bloody civil war from 1936 to 1939.

At the age of 38, during the Civil War, García Lorca was arrested by conservative troops, accused of espionage and immorality. He was executed without a trial and his body was buried in a mass grave, the location of which remains unknown. Lorca's death epitomizes the horrors experienced in Spain during that era.

- See also: Jorge Luis Borges

Early life of of Federico García Lorca

Federico del Sagrado Corazón de Jesús García Lorca was born on June 5, 1898, in Fuente Vaqueros in the Spanish province of Granada, Andalusia. He was the eldest of four children born to landowner Federico García Rodríguez and his second wife, Vicenta Lorca Romero.

Born into a wealthy family, as a child Federico had tutors and piano instructors, and at the age of ten, he was enrolled in a private institute in the city of Granada, where he received a secular education that complemented the Catholic teachings of the Spanish public school. In 1914, while in Granada, he started university, where he studied law, philosophy, and literature, though his true passion at that time appeared to be music, being a skilled pianist.

His university studies awakened new interests in him. He began to frequent a social gathering called "El Rinconcillo" in the famous Gran Café Granada (now Café Alameda), where he met with other students for debates. Under the guidance of Granada-born professor and writer Martín Domínguez Berrueta (1869-1920), he traveled extensively across Spain to Córdoba, León, Burgos, and Castilla, among other destinations.

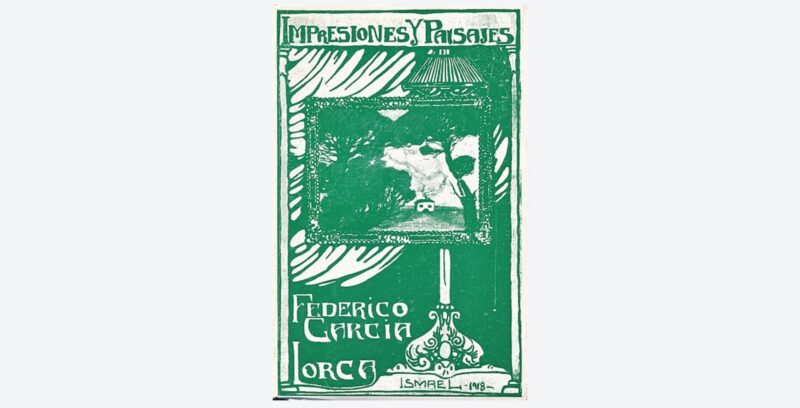

The impressions that these trips made on the young García Lorca was profound, inspiring him to give an account of them in his first book Impresiones y paisajes (Impressions and landscapes), a brief prose anthology published in 1918 on political and aesthetic matters of interest to him. However, his true intellectual formation began the following year, when he joined the renowned Residencia de Estudiantes in Madrid.

Life in Madrid and the Generation of '27

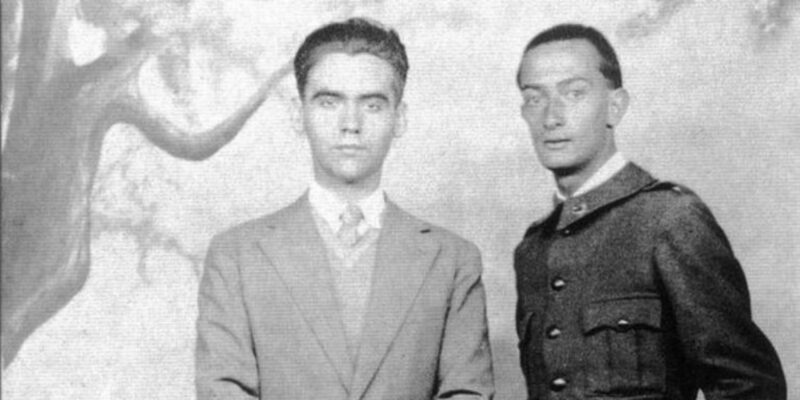

In the early 20th century, the Residencia de Estudiantes in Madrid was a meeting point for local and international intellectuals, as well as for young Spanish talents. From 1919 to 1926, García Lorca mingled with some of the greatest Spanish artists and writers of the time, including Luis Buñuel (1900-1983), Rafael Alberti (1902-1999), Jorge Guillén (1893-1984), Juan Ramón Jiménez (1881-1958), Pedro Salinas (1891-1951), and Salvador Dalí (1904-1989). With many of them, he developed fruitful and long-standing friendships.

Immersed in this intellectual milieu, García Lorca created his early works of poetry, music, and theater. Between 1919 and 1921, he published Libro de poemas (Book of Poems), the play El maleficio de la mariposa (The Butterfly’s Evil Spell), and composed his first suites, brief and avant-garde poems touching upon folkloric tradition, Japanese haiku, and certain poetic trends of the time.

However, Lorca was not satisfied with those early plays. In fact, The Butterfly's Evil Spell premiered in 1920 and was met with criticism and mockery, so its staging closed after only four performances. Even so, the maturity of his talent was already evident in his ability to blend local tradition with avant-garde trends.

In 1922, García Lorca collaborated with Andalusian composer Manuel de Falla (1876-1946) in a cante jondo festival in Granada, an experience that would inspire him to write Poema del cante jondo (Poem of the Deep Song). He also became interested in popular puppet theater, writing the piece Los títeres de la cachiporra (The Billy-Club Puppets).

The major creations during this period were in collaboration with his friend Salvador Dalí. Between 1925 and 1928, Dalí and García Lorca worked together intensely. This proved to be an important relationship for Lorca, in which he confronted for the first time his feelings of homosexual love. On the other hand, his friend helped him to experiment more openly and boldly with words and painting, often coming close to surrealism.

Around this time, García Lorca wrote some more "objective" poems, distancing himself from sentimental tendencies, as was the case with Canciones (Songs) from 1924, or "Oda a Salvador Dalí" ("Ode to Salvador Dalí"), published in 1926 in Revista de Occidente. This "objectivist" poetic approach led him and other fellow writers to revalue the dispassionate poetry of Don Luis de Góngora (1561-1627), to whom they paid public homage in Seville on the occasion of the tercentenary of his death in 1927. Thus was born the name of the "Generation of '27".

A Gypsy in New York

García Lorca’s interest in the theater and the Andalusian tradition, however, did not wane. Between 1924 and 1928, he wrote the plays La zapatera prodigiosa (The Shoemaker's Prodigious Wife), El amor de don Perlimplín con Belisa en su jardín (The Love of Don Perlimplín and Belisa in the Garden) and, encouraged by Dalí, he exhibited a selection of his drawings, of which he had hundreds of sketches.

That same year his famous Romancero gitano (Gypsy Ballads) appeared, a piece that marked his maturity as a poet. It was a lyrical compilation of 18 ballads inspired by the traditional Spanish song, which sold out its first edition within a year and catapulted Lorca to national literary prominence.

The success of Gypsy Ballads, however, brought about one of the deepest crises in García Lorca's life. His fame was such that many pigeonholed him into costumbrismo, or believed him a gypsy or defender of gypsies, who were very much frowned upon by society at the time. Furthermore, his old friends Dalí and Buñuel harshly criticized the work, and in addition, he broke off his romantic relationship with sculptor Emilio Aladrén. All this plunged Lorca into depression, which was compounded by the ban on the premiere of The Love of Don Perlimplín and Belisa in the Garden by the dictatorship of Miguel Primo de Rivera (1870-1930) in 1929.

The Primo de Rivera dictatorship was a military regime that seized political power in Spain on September 13, 1923. Following a coup d'état staged by the Captain General of Catalonia, Miguel Primo de Rivera y Orbaneja, the country came to be ruled by a nationalist military junta that prohibited the speaking of languages other than Spanish and the use of Basque and Catalan flags, censored the press, and suspended constitutional rights and political elections. The de facto regime lasted until Primo de Rivera's resignation in 1930.

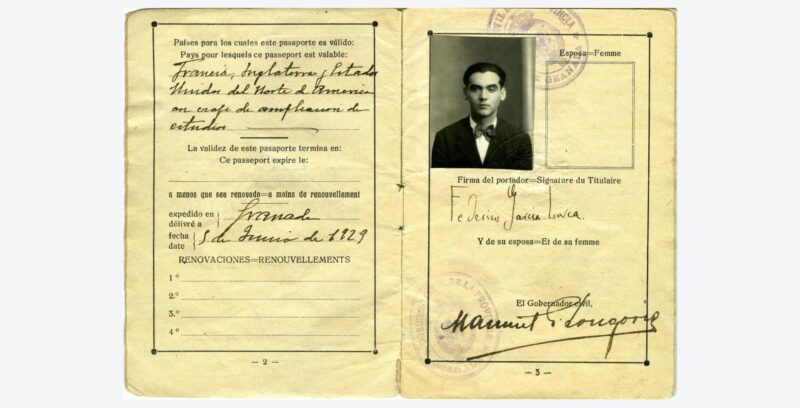

Soon after, García Lorca accepted an invitation from a friend to travel to New York City in June 1929. He stayed there until March of the following year, and wrote his celebrated collection of poems Poeta en Nueva York (Poet in New York), published posthumously four years after his death.

Poet in New York represented a departure from the usual themes of García Lorca's work: a collection of poems written in free verse, filled with hallucinatory images and portraits of urban decay and social inequality. The collection is linked to the works of Walt Whitman (1819-1892), Charles Baudelaire (1821-1867) and T. S. Elliot (1888-1965), among other non-Hispanic poets.

Following his stay in New York, Lorca briefly visited Havana, where he wrote "El público" ("The Public"), a play that openly explores homosexual love. In 1930, the poet returned to Madrid.

La Barraca and the Civil War

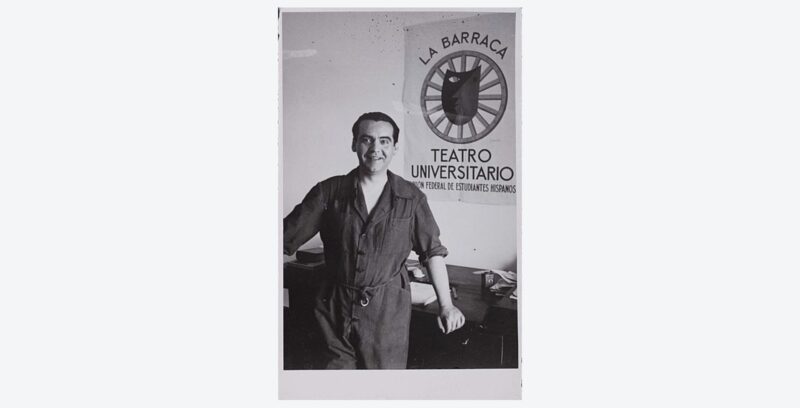

In April 1931, the socialist-oriented Second Spanish Republic was proclaimed, replacing the monarchy of Alfonso XIII. Against this backdrop, new cultural opportunities arose, supported by the Ministry of Education. Among them was the creation of "La Barraca", a university theater group led by García Lorca and writer and theater director Eduardo Ugarte (1901-1955).

Starting in 1932, La Barraca was dedicated to performing the great plays of Spanish Golden Age theater: works by Tirso de Molina (1579-1648), Pedro Calderón de la Barca (1600-1681), Lope de Vega (1562-1635), and Miguel de Cervantes (1547-1616). It was a traveling troupe charged with taking classical Spanish theater to the farthest corners of the country.

Those were highly productive years for Lorca. Not only because of his successful leadership of La Barraca, but because it was during this period that he created many of his most celebrated works. Among them were Bodas de sangre (Blood Wedding), premiered in Buenos Aires in 1933 with Lorca himself present, Yerma, La casa de Bernarda Alba (The House of Bernarda Alba), and Llanto por Ignacio Sánchez Mejías (Lament for Ignacio Sánchez Mejías).

However, the work of La Barraca received criticism from conservative sectors, which accused it of being "socialist propaganda", with García Lorca himself being defamed and insulted by the Catholic press, who mocked his homosexuality. Eventually, he was regarded as an "enemy of the right wing", due to his friendship with important leftist artists and intellectuals of the time such as Rafael Alberti, Pablo Neruda (1904-1973), Salvador Novo (1904-1974), and progressive Spanish politicians like Fernando de los Ríos (1879-1949).

The social and political situation in Spain was extremely tense, and in July 1936 a military insubordination sparked the bloody Spanish Civil War. The last performance of La Barraca took place in the spring of that year at the Ateneo in Madrid. Despite receiving offers of diplomatic asylum from Colombia and Mexico, Lorca decided to return to his family. He was in the Huerta de San Vicente, in Granada, when the military garrison of Granada joined the rebellion.

The execution of García Lorca

When it became evident that he was in danger, Lorca sought refuge in the home of his friend Luis Rosales (1910-1992), whose brothers, members of the Spanish Falange, he trusted. However, it was precisely there that the Civil Guard came looking for him. He was kidnapped and taken to the village of Víznar, locked in an improvised jail, and executed in the early hours of August 18, 1936. He was 38 years old.

García Lorca's body was buried in a mass grave, in some unknown location within that area. Alongside him were executed anarchist militants and the teacher Dióscoro Galindo. Their bodies have not yet been found.

Decades later, in 2015, the execution certificate by Francoist forces was made public. In that document, he was accused of espionage and treason, of being a Freemason, homosexual, and socialist, and it was stated that Lorca had "confessed". Renowned intellectuals including British H.G. Wells (1866-1946) formally requested military authorities for information about Lorca's whereabouts, always receiving a negative answer.

Legacy of Federico García Lorca

Much of Lorca’s work was published posthumously, along with much of his correspondence. Additionally, the murky circumstances of his death inspired numerous elegies and poems by prominent authors such as Antonio Machado (1875-1939), as well as biographies and journalistic investigations.

Efforts have been made to find Lorca’s body, especially after the approval of the Historical Memory Law in 2009, during the presidency of José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero. Yet, all these efforts have been unsuccessful. Numerous memorials and monuments have been erected to honor his memory both in Granada and Madrid.

The work of Federico García Lorca is universally read and acclaimed. His poetry, plays, and prose constitute a distinctive world of their own, intimately related to Spanish folklore and tradition, expressed through a language rich in metaphors.

Lorca's poetry is considered the greatest of the Generation of '27 and is at the pinnacle of Spanish-language literature. It skillfully combines symbols and popular motifs with the forms and trends first of Modernist and later of Avant-garde literature.

Among Federico García Lorca's most notable poetic works are:

- Poema del cante jondo (Poem of the Deep Song - 1921)

- Romancero gitano (Gypsy Ballads - 1928)

- Poeta en Nueva York (Poet in New York - 1930)

- Llanto por Ignacio Sánchez Mejías (Lament for Ignacio Sánchez Mejías - 1935)

- Diván del Tamarit (The Tamarit Poems - 1940)

Similarly, Lorca's dramatic work is considered the most influential in 20th-century Spanish-language theater, alongside that of Ramón María del Valle-Inclán (1866-1936).

His theater is filled with symbols and poetic language, touching upon existential and timeless themes. It tends to follow the theatrical forms of the Spanish tradition: tragedies, comedies, entremeses, puppet theater, and farces, closely bound together with the Spanish Golden Age and Western classical tradition. His plays have been adapted for film and television, and continue to be performed in theaters around the world.

Among Federico García Lorca's most noted plays are:

- La zapatera prodigiosa (The Shoemaker's Prodigious Wife - 1930)

- Así que pasen cinco años (When Five Years Pass - 1931)

- Bodas de sangre (Blood Wedding - 1933)

- Yerma (1934)

- La casa de Bernarda Alba (The House of Bernarda Alba - 1936)

References

- Gibson, I. (1998). Vida, pasión y muerte de Federico García Lorca. 1898-1936. Plaza & Janés.

- Navarro, F. (2023). “Federico García Lorca, músico antes que poeta, el genio también en flamenco y folclore”. El País. https://elpais.com/

- The Encyclopaedia Britannica. (2023). “Federico García Lorca (Spanish writer)”. https://www.britannica.com/

- Sarduní, J. M. (2022). “Federico García Lorca, el poeta brillante que perdió España”. National Geographic. https://historia.nationalgeographic.com.es/

Explore next:

Was this information useful to you?

Yes NoThank you for visiting us :)